My previous post KPI- Part IX: Higher Education in Colonial America highlighted the fairly slow start of higher education in colonial America. In this post, I will address the first age of expansion in American higher education, the post-Revolutionary War era. In the four-score plus years between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, higher education blossomed in the United States on several fronts.

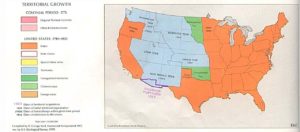

During this period the United States grew both in terms of population and geography. Although there was no census data in 1780, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the population of the thirteen colonies was approximately 2.5 million. By 1860, the 8th official census put the population of the 33 states and several territories, which made up the United States just prior to the Civil War, at 31.4 million. This population increase amounted to more than a twelve-fold increase.

The addition of 20 states and territories added more than 2 million square miles of land mass to the 864,746 square miles of the original 13 colonies. By the start of the Civil War, the United States stretched from “sea to shining sea.” It had crossed the Appalachian Mountains, the Mighty Mississippi River basin, the great plains, and the Rocky Mountains. It spanned the great land gap between Canada and Mexico.

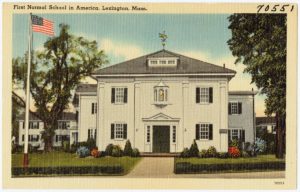

With more people spread out across more land, there is an increased need for primary and secondary education. It was only natural for the people of each town to demand their own local primary and secondary schools. This created an accompanying need for more teachers, which created the collateral need for more higher education. As more teachers are involved in the classrooms, in addition to deeper subject-content matter mastery, they found a need for more specialized training in teaching methods.

This created a need for a new type of higher education institution. Thus the teacher education school or “normal school” was created. Some of these schools were short-lived such as several founded and run by Samuel Read Hall. Hall founded teacher education programs as an adjunct to academies in Concord (VT), Andover (MA), Plymouth (NH), and Craftsbury (VT). The earliest teacher training programs were typically two years beyond the secondary level designed to introduce the best secondary students to the topics of curriculum and pedagogy in order to turn them into teachers.

As noted in the previous post, there were also no “official” medical or law schools in the colonial period. Although several of the colonial colleges did offer additional courses in anatomy and “physik.” they were not intended to train doctors. As the U.S. population grew and spread out all over the country, there was a much greater need for more doctors and lawyers. The apprenticeship model of education which worked well for a small demand proved totally inadequate for the much larger demand of the new world. A new, more efficient, model had to be instituted. We needed a model that would produce consistent, quality results. We needed schools for doctors and lawyers.

The first institution established for the sole purpose of teaching law was the Litchfield Law School in Litchfield (CT). The school was founded in 1874 by educator, lawyer, judge Tapping Reeve. Reeve opened his law school to accommodate the large of apprentices that he was attracting. Judge Reeve continued lecturing at his law school even after becoming the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of Connecticut, until shortly before his death in 1823.

Without the name and draw of its founder, the Litchfield Law School lasted just one more decade until it closed due to lack of students. However, during its sixty-year run of operations, it attracted more than 1,100 students. The most famous/infamous Litchfield graduate is probably Aaron Burr, Jr., the brother-in-law of Tapping Reeve.

As the country grew, so did the demand for more and better buildings, bridges, transportation, and communications. We needed people with technical skills. How could we possibly produce such people in sufficient quantities to meet the demands? We needed technical and engineering schools. Another new type of schools is instituted.

Technical and engineering schools began popping up in urban contexts. Two of the first technical and engineering schools were Norwich University (1819) in Northfield (VT) and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (1825) in Troy (NY).

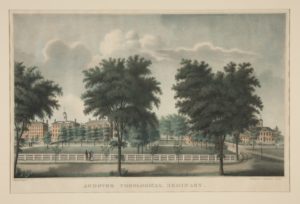

People are people and they must have their religion and their churches. With the population increase and with the dispersion of the population across a wider expanse, there was a need for more churches, and hence a need for more clergy. With the changing nature of the first round of religious schools, America needed schools that were again dedicated to educating individuals who could preach the gospel and teach their congregations the tenets of the faith.

More seminaries and faith-based colleges teaching piety and virtue were created. Due to the lack of action in filling a chair of preaching, on the part of growing faction of liberal faculty at Harvard, a number of the older orthodox, conservative-Calvinistic faculty members left Harvard in 1807 to form the Andover Theological Seminary in Newton (MA). Similar events took place at many of the schools of religion within the Colonial Colleges.

Besides education, religion, and professional studies, one area of concern to the whole human race has been military activities. In the history of mankind, there have been wars and rumors of war. During this era of great expansion of higher education in America, war and military action went to college. In addition to the U.S. Military Academy, established in 1801 at West Point (NY), and the U.S. Naval Academy, established in 1845 at Annapolis (MD), there were at least a dozen more military schools established during this time frame.

In the previous post, I noted that almost exclusively the institutions in the first round of colleges were open only to men. As the nation matured and changed, women understood that education should be open to them.

The first solution to this new demand was the creation of women’s colleges. A few of the earliest women’s colleges were Georgia Female College (1836) in Clinton (GA); Stephens College (1833) in Columbia (MO); and Mount Holyoke College (1837) in South Hadley (MA).

The second solution was a slow opening up of a few of the male-only enclaves to women. Oberlin College (OH) was the first college to formally admit women in 1837. A few institutions, like Franklin College (IN) followed suit in 1842.

During this period of history, the United States was deeply divided over the practices of slavery and segregation. Although slavery was prohibited in all Northern states by 1850, African Americans were routinely denied even basic education through institutionalized segregation.

By 1860 a few colleges were established for African-Americans. These institutions became known as the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1854 was the first HBCU to offer college degrees to its graduates. The first HBCU to be owned and built by African-Americans, Wilberforce University in Ohio, soon followed in 1856. The Cheyney University of Pennsylvania (which was originally called the Institute for Colored Youth) was founded in 1837 and is currently recognized as the oldest HBCU in the United States. However, it did not offer college degrees until 1914. Oberlin College in Ohio is generally credited as the first of the historically white-only colleges to admit African-American students in 1835.

With the vast expansion of the educational enterprise in America, colleges began to engage in the first academic arms race. They began to look for prominent individuals that they could hire to be faculty or administrators, in order to attract a greater number of quality students. States and cities joined in their own version of the academic arms race. Every state, city or town had to have their own college, in order to outdo their neighbors.

All of these changes produced a drastic change in the number of colleges and students. From the ten schools that were really colleges in the colonial period, the number grew to more than 300 by the beginning of the Civil War. The number of college students in the United States is estimated to have grown from less than 2,000 in 1780 to approximately 50,000 students by 1860. This is indeed an era of expansion. Stay tuned for the next installment, the Post Civil War Expansion.

Excellent.

Thank you. I appreciate the affirmation.