Higher education has been around in some form for over two millennia. American higher education is not quite 400 years old. Why does American higher education get all of the hype and publicity instead of our older European, Middle Eastern, and Asian brothers and sisters? How did the younger sibling grow up to be the 800-pound gorilla?

First aside: Q – “Where does an 800-pound gorilla sit?” A – “Anywhere he wants.” The problem with this joke is that most gorillas are less than 6 feet tall and weigh less than 600 pounds. Phil, an Eastern Lowland Gorilla raised in the St. Louis Zoo, is the only recorded gorilla in captivity weighing in at more than 800 pounds.

Second Aside: I must apologize for a mistake I made in my previous post KPI – Part VII: Historical Development of Higher Education, Condensed View. I fell into a trap I was attempting to battle: the myopic view of the world centered on Western Civilization. My error was listing the University of Bologna, founded in 1088, as the oldest, continuous existing, degree-granting university in the world. That title rightly belongs to the University of Al-Karaouine, also written as al-Quaraouiyine and al-Qarawiyyin (in Arabic: جامعة القرويين), located in the Moroccan city of Fes el-Bali. It was founded in 859 by the young Arab heiress, Fatima al-Fihri, to honor the city of her birth and to serve and educate the community that welcomed her and her family as emigrants.

Aside three: Surprise! Surprise! As I wrote this post, I found that I couldn’t condense the history of American higher education into 1,000 words. Thus I will deal only with its European foundations in this post. I will use my next post to pick up the story on American shores with the founding of the “Colonial Colleges.” That story will start with Harvard College in 1636. I may be able to use that post to get us to the 19th Century. From there I will need at least one more subsequent post to carry us to the higher education scene in America today.

One of the drumbeats of proponents of modern American higher education is the constant encouragement for students to attend a university to obtain a broader vision of the whole world. Students are bombarded with advertisements urging them to spend a semester or year abroad to break down the insular barriers isolating them from other cultures.

It may be ironic that American institutions of higher learning trace their education model and form of organization to a single archetype. In doing this, they are ignoring the traditions of most of the world that they are commending to their students.

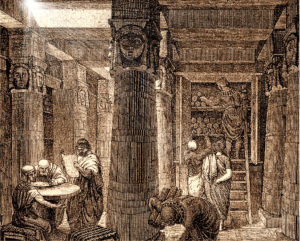

The sole archetype is a system epitomized by the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, and the European form embodied by the University of Bologna and the Sorbonne (or University of Paris). In this system, faculty with similar interests gather themselves into colleges in order to stimulate each other to create new knowledge, organize existing knowledge into understandable formats, and disseminate that knowledge as widely as possible.

These colleges recruit and admit students to their ranks based upon students’ identity with the interests of the faculty. The colleges provide academic facilities for the faculty, such as classrooms and offices. They are also responsible for providing housing and boarding facilities for the students, and some faculty.

In their earliest years, the British colleges required students to commit themselves fully to their education. This meant that students had to “live” in the residence halls and be available on a 24/7 basis. Everyone, students and faculty, ate formal meals together. This permitted extended academic discussions to take place over the course of the meals. Many faculty lived on campus which meant that education could occur around the clock.

The separate colleges established a collective, called a university. Whereas colleges set their own curriculum and courses, the university set some minimal standards for degrees and conferred those degrees. Students could take courses in other colleges to complete their education. Most likely, only one college within the university offered music courses and programs. It was also likely that religion and philosophy courses were consolidated within one college. The disciplines of science, mathematics, humanities, literature, social sciences, law, and medicine would have had their own specialty colleges.

Right from their earliest days, religion was an integral part of Oxford and Cambridge Universities. All faculty had to be communicant members of the Catholic Church. Students were required to attend religious services and receive instruction in religious matters.

Somewhat surprisingly in their formative years, the continental universities were not tied formally to the church. They also did not have housing for students. Students lived in the community, which resulted in many conflicts with the “townies.”

In both the British and European universities the faculty were the formal masters of the organizations. Every major decision was decided either by consensual agreement or a vote of the faculty. From this arrangement, American higher education derived its ideal of faculty governance.

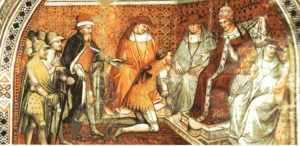

When the University of Bologna was founded, it was established as a school that was free from ecclesiastic control. In 1158, Frederick I Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, issued a writ which became known as the Privilegium Scholasticum. Among its provisions, this law declared that every school should be a group of students overseen by a master (dominus). This master teacher was to be paid through monies collected from the students. These payments were the first tuition charges.

The submission of Frederick I Barbarossa, protector of the University of Bologna, to the authority of the Roman Catholic Church, in order to secure his position as the Holy Roman Emperor, began two centuries of political wrangling among the faculty of the University of Bologna. It only subsided with the establishment of the School of Theology in 1358. For the next five centuries, Roman Catholicism was an integral part and a significant player in the life of the University.

Another provision of the Privilegium protected faculty and students in their pursuit of knowledge from the intrusion of all political authorities. This was a fundamental event in the history of the European university. The University has legally declared a place where research and new knowledge could develop independently from any other power. This was the beginning of the concept of academic freedom.

Finishing off this post, I will take leave of the palaces, halls, cathedrals, colleges, and universities of Europe and migrate to shores of the New World in North America. In my next post, scheduled to be published on Friday, April 5, I will look at the early development of American higher education