There are five distinct periods in the history of American higher education. In this post, we will look at the initial stage, which we will call the Colonial Period. The beginning date is easy to set. It starts with the founding of the first American college, Harvard College, in 1636. The end date is much harder to define. We will arbitrarily set the ending date of this stage as 1776, the start of the Revolutionary War. As we shall see, using these dates makes the Colonial Period the longest and least active stage in the history of American higher education.

The academy is well known for its showy, even often ostentatious traditions and “pomp and circumstance.” By “pomp and circumstance” I don’t mean the Elgar military marches played at graduation or commencement ceremonies.

One long-standing tradition of the academy involves the ceremonial inauguration of new presidents or the opening of a new college. To celebrate this joyous occasion, other colleges are invited to send a representative to share in the festivities.

These visiting representatives are expected to wear appropriate academic garb (their caps and gowns) and march into the ceremonial arena following the representatives of the new college or institution installing its new president. These representatives include the governing board, the president, high ranking officers of the college and the college faculty.

The representatives of guest colleges are lined up according to the founding date of the particular institution, with oldest first. Thus it becomes a bragging point to be near the beginning of the line. Many institutions take this so seriously that they “may stretch the truth a little.”

My alma mater, the University of Delaware, could be accused of falling prey to this practice. It lists its date of origin as 1743, which is embossed on its seal. This date would make it the eighth oldest college in the United States. In reality, according to its website the University of Delaware:

One of the oldest universities in the U.S., the University of Delaware traces its roots to 1743 when a petition by the Presbytery of Lewes expressing the need for an educated clergy led the Rev. Dr. Francis Alison to open a school in New London, Pennsylvania.

In 1765, Rev. Alison’s elementary and secondary school relocated to Newark, DE, as the Newark Academy. It wasn’t until 1834 when the name was changed to Newark College that the institution offered college degrees. In 1843, the name of the institution was changed to Delaware College. Throughout all of its earliest history, the institution was opened only to men. In 1914, a women’s college was opened in Newark. The two colleges merged in 1921 to become the University of Delaware. I’ll let you decide: What date should the University of Delaware use as its date of founding?

So as to not be accused of just jumping on the University of Delaware, of the 18 American colleges or universities that list a founding date prior to 1776, only ten were actually conferring college degrees in 1776. These ten colonial colleges with dates of their founding are:

- Harvard University. MA (1636)

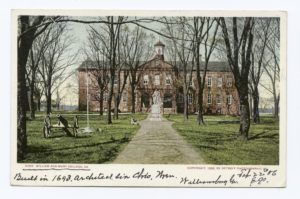

- College of William and Mary, VA (1693)

- Yale University, CT (1701)

- University of Pennsylvania, PA (1740)

- Princeton University, NJ (1746)

- Columbia University, NY (1754)

- Brown University, RI (1764)

- Rutgers University, NJ (1766)

- Dartmouth College, NH (1769)

- Hampden-Syndey College, VA (1775)

The eight institutions which list a date of origin prior to 1776, but didn’t offer programs leading to college degrees until after 1776, are the following:

- St. Johns’ College, MD (Est 1693/ College 1785)

- Washington College, MD (Est 1723/ College 1782)

- Moravian College, PA (Est 1742/ College 1863)

- University of Delaware, DE (Est 1743/ College 1843)

- Washington & Lee University, PA (Est 1749/ College 1813)

- College of Charleston, SC (Est 1770/ College 1790)

- Salem College, NC (Est 1772/ College 1890)

- Dickinson College, PA (Est 1773/ College 1783)

As a mathematician, I am always looking for patterns. In the case of these pre-revolutionary war colleges, several patterns are immediately obvious. All 18 institutions were founded by clergy or religious organizations for partially sectarian reasons. The primary religious reason was to provide an educated clergy for the churches. Since the pre-revolutionary war clergy was all male, it should not be surprising that 16 of the 18 colleges were strictly male institutions. The only two schools which enrolled women were the two Moravian institutions, Moravian College and Salem College.

Interestingly those are only two that have maintained their religious affiliations. The other 16 either dropped their religious ties or had their support cut off by their founding denominations. Thirteen of these schools changed their classification to “private, non-profit“. Two of the schools, Rutgers University (NJ) and the University of Delaware (DE) became public institutions supported by their respective states. The College of Charleston (SC) became the first college in the United States to be recognized as a municipally supported school.

Later, when the State of Delaware cut its monetary support of the University to less than 50% of the University’s budgeted income, it took a drastic step which defined a new status of educational institutions. The University of Delaware became the first college to become a private institution with limited state support. It was now known as a “state-supported institution.” Since that event, many other public schools have taken the same stance.

Another characteristic shared by all 18 pre-revolutionary war colleges is that they all began as exclusively residential or boarding schools. Most of the founding fathers of these schools were educated in England or Europe or were swayed by teachers or mentors who were trained in the “old-school” tradition.

The “old-school” traditions imparted two patterns into the fabric of these schools. The first was the idea that these schools were not about promoting or advocating social mobility. These schools were not founded to change society, but to maintain the social status of the day. After their religious ties were severed, their students were strictly the sons of the wealthy, politically connected, and social elite of the day.

These were the only families that could afford the cost of such an education. These families were also the most interested in preparing their sons to claim their birthright and seize their rightful place as leaders of the church, government, and business. It is interesting to read excerpts of early promotional pieces of these institutions and see how many advertised the alumni who were instrumental in the founding of America. They listed the signers of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States, as well as federal, state and municipal elected and appointed officials as their most distinguished graduates.

The second pattern inherently obvious among the colonial colleges is the emphasis of their curricula on the liberal arts. Many of these colleges evolved from institutions that were called “Free Academies.” The term free definitely did not refer to the cost of attending the school. The term refers to the liberal arts or those subjects which humanize people and make them more human.

The curricula were heavily loaded with rhetoric, languages, religion, philosophy, history, music, mathematics and elementary science. In the colonial period, there were no professional schools. The professional disciplines were not taught at the colonial colleges.

Students who were interested in business, law, and medicine learned these “trades” by serving as interns to accomplished masters. The professional schools entered the American higher education scene in the next period of American higher education history, the Period of Post-Revolutionary War Expansion. That period will be the subject of my next blog post, due to be published, Tuesday, April 9th.