My previous post, Greeting on New Year’s Day 2021, outlined an ambitious plan for me. That post checked off the top item on “MY WANT TO DO LIST, January 1, 2021.”

As we enter into a new year and attempt to navigate uncharted waters, I offer everyone a “Twelfth Day of Christmas” gift. I believe this suggestion can make completing tasks a more rewarding experience. I’m not saying this hint will work for you. However, it has been beneficial to me. I have changed the title of my “[HAVE] TO DO LIST” to “MY WANT TO DO LIST.” The corresponding attitude change has been enormous and has helped me accomplish so much more, especially in light of [my wife] Elaine’s battle with non-Hodgkins Lymphoma this past year.

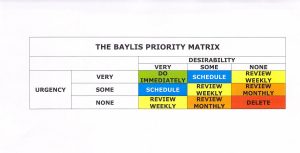

There are still days when I don’t get to everything on my list because unforeseen emergencies can arise that I must address immediately. However, if something comes up that is not urgent nor desirable, it is much easier for me to pass on it.

I usually scan my emails and social media accounts twice a day, early morning and late afternoon. As part of that routine, I single out ones that I must or want to read immediately. Although writing is critical to me, maintaining contact with individuals is also still crucial. If there is something that I should and can do immediately, I take care of it. If I see something I may want to reference in my research or writing, I file it in a labeled subfile to take care of later. I immediately delete those that I know are of no interest or urgency. It usually takes me one hour a day to go through this procedure.

My other emails I divide into two unread subfolders. The first contains those that I will more thoroughly evaluate the next Friday. The second subfolder contains those emails that I will look at again at the beginning of the following month. By the time I go through these emails, I can delete most of them since they are no longer relevant nor what I envisioned them to be. However, there are others in which I will find a small gem of an idea that I need to take care of then or file away for future use. I usually spend one to two hours on Fridays and three to four hours at the beginning of each month cleaning out my inbox.

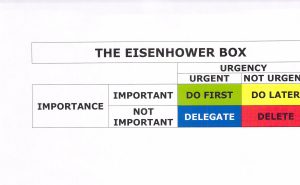

My process is a variation that I adapted from the decision matrix known as the Eisenhower Box. In his position as a general of the U.S. Army, and later as President of the United States, almost everything that came to him was critical to someone. These tasks had to be cared for by somebody at some level. So he developed a procedure to ensure that somebody gave proper and timely attention to the matter.

In his leadership roles, Eisenhower enjoyed the benefit of a large corps of subordinates. In all of his leadership positions, he was surrounded by a large, capable staff that was always present to assist him and to whom he could confidently delegate tasks. As a retired higher education administrator, researcher, and writer, I don’t have this luxury. I work alone. I have no one to whom I can delegate tasks.

Returning to the day after Christmas, by the time I was drinking my first cup of coffee at breakfast, I fell into one of those “little kid’s moods.” I had lots of questions flying around in my mind about the coming new year. All of them were concerned about the coming year, 2021. You know the questions: “Who?” “What?” “When?” “Why?” “Where?” and “How?” You also probably recognize them as the six questions that your 7th grade English teacher drilled into your head that every essay should answer.

They are also the six “W” questions journalists should attempt to answer in any article they write. Wait a minute! The adage for journalists concerned the five necessary “W” questions that their work must answer. I threw one extra question into the mix. I know it doesn’t start with “W.” However, it does end with “W.”

My first question was, “How did we get the calendar we rely on for so much of our lives?” My list of questions grew exponentially. The history of our modern calendar is a long and convoluted journey. Various strands began in ancient Persia, China, India, Egypt, Judea, Greece, Rome, and Mesoamerica.

Each of these civilizations noted that there were reoccurring cycles in nature. The regular alternation of light and darkness was the first cyclic pattern that everybody recognized. The sun “came up” and “set” with surprising regularity. While the sun shone, people could see to work. When the sun was not shining, they stopped working. They “called it a day” and went to sleep.

The idea of a day predates humanity. God introduced it “In the beginning.”

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.[Genesis 1:1-5, KJV]

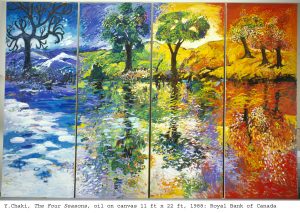

The second major cycle that people noticed was the four seasons. Plants went from a dormant state to showing signs of life, to full bloom, to their dying stage. With this cycle, three cyclic phenomena coincided. As the ambient temperature became warmer, the length of time the sun dominated the sky and brought light to the world became longer. As it became colder, days became shorter, and nights became longer. People also noticed that the pattern that the sun traced across the sky changed in predictable ways during these seasonal changes.

Over time, as people kept track of these three cycles of the sun, it became evident that they were approximately 365 days long. This discovery became the basis of our current year.

Another major cycle that became apparent was how the moon’s shape changed in the night sky. It went from not visible, growing into a full circle, and then shrinking again to nothing. Continuing observations determined that the moon or lunar cycles took approximately 28 days. These lunar cycles introduced the concept of months.

It also soon became apparent that the solar and lunar cycles did not line up or connect very well. The number of lunar cycles varied from year to year.

It took trained observers many cycles and years to find a fifth major cycle in the sky. Although the sun and the moon dominate the sky and claim most of the attention, stars have fascinated humans from the earliest recorded history.

How often have you said, “That cloud looks like a bunny rabbit?” If one stares at things like clouds and stars long enough, one will start seeing patterns. With only a little to no indication of cross-fertilization of ideas, sometime between 3000 and 500 BC, the civilizations in North Africa, Babylon, China, and Mesoamerica began to notice individual stars’ groupings stayed reasonably constant in relation with one another. People started to see figures in the sky outlined or highlighted by these groups of stars. These figures were the beginning of the concept of constellations.

In the above paragraph, I was cautious to note that the stars stayed relatively constant in their relative position with one another. Before 1300 BC, sailors and land travelers were using specific stars and constellations to help them find their way from one place to another. The term lodestar refers to a guiding principle. Polaris, also known as the North Star, is used in the Northern Hemisphere as a lodestar to help people find their direction.

However, as years and centuries passed, the overall position of stars and constellations in the sky changed in a very regular pattern. Unfortunately, this star-cycle did not coincide with a single year but a group of years. Star-cycles began to take on a life of their own.

By 1300 BC, various civilizations all over the world had identified more than 30 constellations. The Book of Job, arguably the oldest book in scriptures, references specific stars and constellations.

Can you bind the chains of the Pleiades? Can you loosen Orion’s belt? Can you bring forth the constellations in their seasons or lead out the Bear with its cubs? [Job 38:31-32, NIV]

The NIV translates the Hebrew word Mazzaroth (מַזָּרוֹת Mazzārōṯ, LXX Μαζουρωθ, Mazourōth) as “constellations in their season.” The literal meaning of the phrase is “garland of crowns.” It is found in other ancient Hebrew works referring to the Zodiac and the constellations that constitute it.

By 500 BC, the Persian, Greco-Roman, Chinese, and Mayan civilizations used the same 12 constellations as markers for a stellar (or star-based) year. As noted above, these star years were out of sync with the solar and lunar years. Since the solar calendar had more days than the lunar or stellar calendars, the four civilizations tried many different approaches to compensate for those lost days.

Eventually, the Greco-Roman world gave up trying to reconcile the differences among the solar, lunar, and stellar calendars. It relegated the stellar calendar to the world of astrology. Astrologers embraced it and used it to explain aspects of persons’ personality and predict significant events in their lives based on celestial objects’ positions when they were born.

Astrology has a very complicated and contentious history. Since this blog post deals with our modern calendar’s construction, I leave the world of astrology and stellar cycles and years to another post.

In 46 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar, in an attempt to unify the world under Roman control, issued an order that everyone must use the calendar he designated. Sosigenes, a well-known Greek mathematician and astronomer reportedly constructed this calendar under Caesar’s direction. In addition to his training in the Greek traditions, Sosigenes lived in Egypt and was trained in Ptolemic conventions.

The Julian calendar consisted of 365 days divided into 12 months of varying lengths, except it added an extra day every fourth year to make it more in line with solar solstices and equinoxes. Does this sound familiar?

To honor the “two-faced” Roman god, Janus, the year started on January 1. Having eyes that simultaneously faced two opposite directions, Janus was adept at reflecting on the past and planning for the future. This is a tradition that we still hold onto with our New Year’s resolutions.

The European world used the Julian calendar for more than 1600 years. In the late 16th century AD, the Catholic Church’s ecclesiastical calendar and feasts were noticeably out of sync with the solar calendar’s fixed points.

At this point, Pope Gregory XIII intervened and ordered the Church to use a variation of the Julian calendar that made two changes. Since the Catholic Church was the predominant force in Europe, except for Great Britain, which had split from the Church of Rome and formed the Church of England, Europe was again operating on two different calendars.

The first change was to lower the average number of days per year from 365.25 to 365.2425. The new Gregorian calendar did this by eliminating three leap days every four centuries. It did this by keeping a leap day in every calendar year that is evenly divisible by four, except the years that are not divisible by 400. Thus, the years 1700, 1800, and 1900 had 365 days, while 2000 had 366 days.

Although this brought the calendar year significantly closer to the solar year, the solar year is the time between two successive occurrences of the vernal equinox, the moment when the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator moving north. This is approximately 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 46 seconds. If we kept the extra leap day in our calendars every four years, four calendars would be 14 minutes and 4 seconds longer than four solar years.

At this difference rate, the calendar year would be almost one hour shorter every 16 years. This translates to losing a day every 400 years. Thus, the dropping of Leap Day in centuries divisible by 400. However, this is still inaccurate. Under this system, the calendar year will be off one day every 3236 years. Since the oldest man in the Bible, Methuselah, only lived 969 years, I don’t think any of us will have to worry about recalibrating the Gregorian calendar around 5000.

I have skipped over most of the complicated mathematical computations that went into constructing the Gregorian calendar. I believe the few examples of the difficulties that I have provided proves that the answer to the question, “How did we get our modern calendar?” is far beyond the scope of a simple blog post. In my next post, I will move on to the question, “Why is January 1 designated as the beginning of a new year?”