After each major war in the history of the United States, significant growth occurred in the American higher education enterprise. All of these increases combined did not equal the growth in the three decades following WWII. The period between 1945 and 1975 could easily be labeled the Golden Age of American Higher Education.

During this time span, American higher education had the Midas touch. Everything was going well. American colleges and universities had overflowing enrollments. They couldn’t build facilities fast enough to satisfy the undergraduate student demand. Graduate schools couldn’t produce a sufficient number of PhDs to fill the faculty positions needed to teach the surfeit of undergraduate students. Public and private supporters tripped over each other as they rushed to provide the enormous increase in financial support needed to finance the vast expansion occurring. Nationally and internationally the reputation and prestige of American higher education were soaring to new heights.

During these three decades, the face of American higher education (AHE) was completely altered. AHE changed its focus. No longer was it predominantly an exclusive club for the sons of the wealthy elite, providing them with a liberal arts veneer to establish and ground them so that they could assume their “rightful place” of leadership in business, governmental, ecclesiastical, and social circles.

As WWII wound down and the nation transitioned into a post-war phase, two presidential actions had an enormous effect on American higher education. The first occurred two weeks after the Allied landing on the beaches of Normandy, France on D-Day, which began the most important battle of the war. On June 22, 1944, President Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, into law. This bill provided a very wide range of benefits for returning World War II veterans, including educational assistance for veterans and their families.

This law expired in 1956 and was subsequently replaced by adjustments for veterans of the Korean Conflict and Vietnam War. Of the nearly 16 million World War II veterans, more than 2.2 million used benefits to enroll in a college or university and another 5.6 million participated in various career-oriented training programs. In the peak year of 1947, veterans accounted for 49 percent of all U.S. college admissions. Between 1956 and 1975, another 6 million individuals were aided by educational assistance programs for veterans and their families through extensions to the original GI Bill.

In light of the economic, demographic and educational changes occurring in the United States, by proclamation on July 13, 1946, President Harry S. Truman instituted a Commission on Higher Education, and named George F. Zook, then president of the American Council on Education, as its Chair. Truman charged the Commission

“…to concern itself with the ways and means of expanding educational opportunities for all able young people; the adequacy of curricula, particularly in the fields of international affairs and social understanding; the desirability of establishing a series of intermediate technical institutes; and the financial structure of higher education with particular reference to the requirements for the expansion of physical facilities.”

In the Commission’s 1947 Report, Higher Education for Democracy, it was noted that

“Education is by far the biggest and the most hopeful of the Nation’s enterprises. Long ago our people recognized that education for all is not only democracy’s obligation but its necessity. Education is the foundation of democratic liberties. Without an education citizenry alert to preserve and extend freedom, it would not long endure.”

The last phrase echoes the words of President Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the Gettysburg Civil War Battlefield Cemetery.

In reflecting on President Truman’s charge to the Commission, the report stated that

“…the President’s Commission on Higher Education has attempted to select, from among the principal goals for higher education, those which should come first in our time. They are to bring all the people of the Nation:

-

Education for a fuller realization of democracy in every phase of living.

-

Education directly and explicitly for international understanding and cooperation.

-

Education for the application of creative imagination and trained intelligence to the solution of social problems and to the administration of public affairs.”

In spite of the new frontiers in to which American Higher Education was being pushed by the perceived new national needs and the plethora of government commissions, reports, and programs, along with the burgeoning population growth engendered by the Baby Boom and subsequent diversification of the potential higher education clientele, AHE still proclaimed itself as the legitimate heir and guardian of the liberal arts tradition. The only concession that AHE seemed willing to make was the introduction of the new model of a liberal education to replace the declining model of the ancient liberal arts.

The seven traditional liberal arts of Medieval times were divided into two parts. The first part was called the trivium, which consisted of three literary disciplines. The second part was called the quadrivium, which consisted of four quantitative disciplines.

The three literary disciplines were:

- Grammar. This deals with the correct usage of language, both in speaking and writing.

- Dialectic (or logic). This is correct thinking, helping an individual arrive at the truth.

- Rhetoric. This concerns the expression of ideas, particularly through persuasion. It deals with ways of organizing thoughts in a speech or document so that people can understand your ideas and believe them.

The four quantitative or mathematical disciplines were:

- Arithmetic. This deals with numbers and the simple operations involving numbers.

- Geometry. This concerns spaces, spatial calculations, and spatial relationships.

- Astronomy. This is the study of the stars. It is used for timekeeping, navigation, and developing a sense of place.

- Music. This is the study of ratio, proportion, and sound as it is related to melody and song.

Prior to the 20th-century, with a few exceptions for professional and practical arts programs, American higher education followed the medieval liberal arts paradigm. In the 20th-century, American society transitioned from a rural and agricultural society to an urban and manufacturing culture. In response to these changes, AHE evolved along with them.

The 20th-century American higher education version of the liberal arts added several other components. These were usually framed in the sense of the answer to the question: “What foundation of general knowledge did a well-educated individual need?” These additions began with a solid grounding in the humanities and sciences, including history, philosophy, the social sciences, and the natural sciences. AHE invented the term liberal education in an attempt to describe this “slightly altered” form. To describe this new form of education, the term liberal designated the knowledge and values which freed up or liberated an individual to be more human or humane. The American Association of Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) took it upon itself to define more fully what the new liberal education should look like and involve.

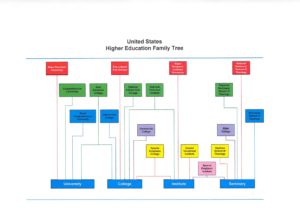

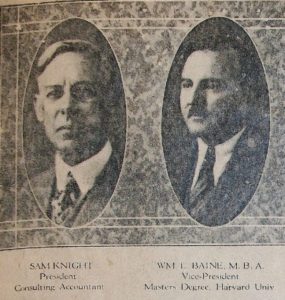

American higher education became bifurcated and unapologetically splintered. While one side of campuses persisted as the solid, unyielding fortresses of the liberal arts and liberal education, the other side of campuses rapidly developed into the training ground of choice for a quickly and constantly changing workforce which needed professional, technical, and career knowledge and skills. Students flocked to American colleges and universities to study the practical arts and sciences (such as the agricultural sciences of horticulture and animal husbandry), engineering, technology, educational studies (such as pedagogy and curriculum), and career and professional studies (such as accounting, business administration, and management).

In each of the two camps of the liberal arts and the practical and professional studies, more fissures appeared. Both camps separated themselves into undergraduate and graduate schools. The undergraduate schools concentrated on providing students with basic post-secondary education, helping them acquire the skills and knowledge necessary for further study or to obtain the first position in their field. The graduate schools concentrated on assisting qualified students to do more in-depth study within their field and prepare themselves to add to the world’s knowledge base.

American higher education had expanded its reach after the Civil War into the service arena with the Land Grant Act. University faculty were also drawn into national service through research projects directed toward the national defense in the lead up to WWII. After WWII these areas exploded. Rising revenues from government and industry sources transformed faculty research from an afterthought into a booming business.

President Kennedy was the superb politician and master of the one-liner. He spurred the nation into a service frenzy, with his “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” The peace corp, an outgrowth of Kennedy’s inaugural speech, became the embodiment of the ideals toward which the Morrill Act of a century earlier had pointed a growing nation.

Kennedy then jump-started the space race in his famous Rice University speech with the line: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard…” This challenge set the tone for a decade of exploits not only in space travel but many other areas of scientific and medical research in which American research universities led the way.

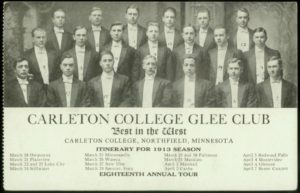

The American research university came into being in the late 19th century as a few American institutions took the German Humboldt University model and put a new world twist on it. In February 1900, the presidents of five American universities (Chicago, Columbia, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, and the University of California) invited the presidents of nine other universities (Catholic University of American, Clark, Cornell, Princeton, Stanford, University of Michigan, University of Pennsylvania, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Yale) to meet at the University of Chicago to discuss plans to solidify the place and reputation of American universities in the research and higher education world. As a result of these discussions, the fourteen schools formed the Association of American Universities (AAU).

The initial agenda of the AAU included three items:

- to bring about “a greater uniformity of the conditions under which students may become candidates for higher degrees in different American universities, thereby solving the problem of migration,”

- to “raise the opinion entertained abroad of our own Doctor’s degree,” and

- to “raise the standard of our own weaker institutions.”

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, as the American research university matured, the unofficial agenda of the AAU became the following four points:

- inspire research institutions to emphasize a distinction between preparatory studies and higher learning;

- encourage research institutions to make the idea of advancing knowledge through specialized, original research a central tenant of their mission statements;

- embolden research institutions to assure the independence of faculty and students in the area of intellectual inquiry (i.e., guarantee “academic freedom” in their studies)

- exhort research institutions to provide the necessary institutional structure to fully support the “research ideal.”

After WWII, the AAU redoubled its efforts to push a “specialized research” and an “America first agenda.” Although world rankings of universities didn’t exist until several years into the 21st century, the 60 United States members of the AAU were recognized around the world as top-flight educational institutions. By 1975 these schools and many other American colleges were attracting students and faculty from every corner of the world.

To many inside and outside the American higher education community, the horizon for American higher education could not have looked brighter. However, to the critics and some commentators of AHE, warning signs abounded. There was a storm brewing that was just showing up on radar screens across American campuses. Just like the radar screenshot of Tropical Storm Humberto shown at the left, only small showers had landed prior to the approach of the massive body of the storm, which was getting ready to unload its full fury a short time later. Was the golden age of American higher education about to end? Spoiler alert: my next post in this series will focus on the disruptive forces which played havoc with American higher education from 1975 to the present.