For my third post of the year 2021, I will be looking at two teasingly simple questions. With so much going on in the world this month, I will be the first to admit that my questions are not earth-shaking inquiries.

You may ask, “Why, at this time, am I concerned with such a seemingly trivial matter?” The world is staggering under the burden of a deadly pandemic. The United States is embroiled in social unrest over many issues. The country is reeling from one crisis after another. People are continually expressing their discontent through words and actions. Almost everyone is constantly murmuring in disgust about the political dissension and hypocrisy, evidenced at all government levels.

However, almost three weeks into a year for which we had such great hopes, we find ourselves struggling with many of the same disappointments of this past year, along with a huge, new portion of disillusionment. I am already tired of the endless chatter, unrestrained finger-pointing, and futile arguments. I am stepping away from the podium and microphone. I am ready for a break.

My two questions are

- Why do we celebrate January 1 as the start of a new year?

- Who decided this for us?

As I thought about the perfect time to start a New Year, I found many good possibilities. In fact, many organizations and activities use different dates for the start of their years. These dates are based on the cycles we encounter in our daily lives.

Since I live near the 40° latitude North and 77° longitude West, I will use dates and events associated with that part of the world and my interests.

Before the pandemic, February 1 was generally considered the start of the automotive racing season and the opening of spring training for baseball. In my geographic part of the world, cold weather is a staple of February. Snow is a distinct possibility. Since neither of these weather-related events is conducive to enjoying or playing these two sports, teams head south or west to begin their year.

March 1 is the meteorological start of the spring season. It is also the beginning of a new cycle of life for many plants. March 21 is the spring or vernal equinox. This is one of two dates in a year when the hours of daylight and nighttime are equal.

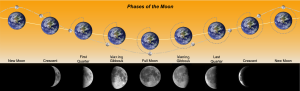

Depending upon the lunar calendar, Easter occurs in March and April. Easter is the celebration of resurrection and a new life. According to church tradition, Easter is observed on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox.

April 1 used to be the unofficial start of the baseball season. Before 2000, Major League Baseball had to extend their season into March to get the required number of games before winter weather threatened the World Series. High schools and colleges started their outdoor spring sports season on April 1 to finish before the school year ended.

Growing up, I remember April 1, not as April Fool’s Day. It was the day we could take our studded snow tires off our cars and use regular tires. Peace and quiet returned to the roads.

By April 1, we always had our garden plans in place. We would plant the vegetable seeds in the indoor growing beds. April was the month to bring our lawn tools out of hibernation and tune them up for the upcoming work. It was also the time to prepare the soil in our garden for another growing season.

The last killing frost of the winter season typically occurred in early April. We always had to rush to get our pea seedlings planted as soon as possible after that last frost. Other seedlings could wait until the end of April or the beginning of May. For plants started from seeds, those seeds had to be planted before the end of April.

The third Saturday in April is the opening day of the open trout fishing season in Pennsylvania. For many fishing enthusiasts, this is a Red Letter Day on their calendars.

May 1 is generally the start of the blooming season for many fruits, vegetables, and flowers. Tulip festivals are held in many locations in early May.

May is also graduation and commencement month for educational institutions and their students. Commencement is a time of new beginnings for graduates. Beginning a new phase in life seems like a good time to start a new year.

June 1 is the start of summer and the usual vacation season. Growing up, our school year was always done by June 1. June 21 is the summer solstice or longest day of the year.

In many organizations, July 1 is the start of many fiscal and budgetary years. July 4 is American Independence Day and the Birthday of the United States of America.

I looked extensively to find something special about August. I came up empty-handed. It just sits there and does nothing. It has the well-deserved nickname “dog-days of summer.”

September 1 is the unofficial start of the harvest season and most fall sports. It is the start of the meteorological fall season and the end of summer. In the United States, the first Monday of September is Labor Day, celebrating the industrious American worker.

The month of September is also the start of many scholastic and ecclesiastic years. Schools, churches, businesses, and families “return” to a “normal” schedule.

September 22 is the autumnal equinox, the moment when the sun is exactly over the equator. It is the second time in each year when days and nights are of equal lengths. This is the official start of fall.

October is another month like August. Although several events regularly occur in October, there are not many openings or firsts. October is known for fall harvesting of plants like corn, pumpkins, soybeans, or wheat. In our part of the country, it is also known for small game hunting. For children, October is also the home of Halloween and Trick or Treat. At the end of the month, the church celebrates All Saints’ Day.

November is generally the time for elections in the United States. It is also the month reserved for Thanksgiving and many harvest festivals. In Pennsylvania, for many years, the first Monday after Thanksgiving was the start of rifle deer season. This year the State Game Commission moved the start of rifle deer season to the first Saturday after Thanksgiving. The first Monday of deer season is still a school holiday in much of Pennsylvania. Many years ago, this tradition was established so that teachers and students could harvest deers as food for the long winter ahead.

December is the month of Christmas and Advent, the coming of God to earth. It is not just December 25. It is a whole month of joyous celebration of Emmanuel, “God is with us.”

December 21 is Winter Solstice, the shortest day of the year. It is a day when the earth gets to enjoy its time of rest. If we were to follow the Jewish tradition of beginning a new day at sunset, this becomes a prime candidate as the official start of a new year.

Other geographic places and religious traditions have their own special dates. Many of them celebrate a date other than January 1 as the start of their New Year. Thus there are scores of choices for celebrating a New Year.

I was somewhat surprised to discover that the answer to my two questions pointed to two apparently disparate individuals.

These two individuals lived more than 15 centuries apart. One led a political world empire. He was declared a god and worshiped by his subjects. The other led an ecclesiastical empire. He viewed himself as a servant of the one true God. The members of his church saw him as God’s messenger.

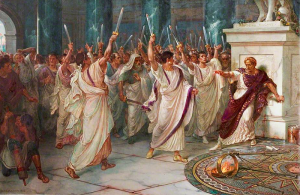

We can thank Julius Caesar (46 B.C.) and Pope Gregory XIII (1582 A.D.) for enshrining January 1 as New Year’s Day. Each of these powerful leaders ordered the world they controlled to use a single calendar that they chose. Due to the percentages of the world under their jurisdiction, they dominated most of the world of their times.

Julius Caesar was the dictator of the Roman Empire from 49BC to 44BC. In March 44BC, he was assassinated by Roman Senators led by his supposed friend and ally Brutus. Because of problems in the first years of his dictatorship, Ceasar wanted the world to use a single calendar. He saw the usefulness of a single calendar for political, fiscal, and military reasons. The Roman Empire was 3000 miles from end to end. It spread across most of southern Europe, coastal Asia Minor, and Northern Africa.

Coordinating events across such an expanse required precision. Caesar wanted taxes collected and censuses taken simultaneously in all corners of the empire. This way, people couldn’t escape the government’s strong-arm by fleeing to other parts of the empire. He also wanted military attacks synchronized so that enemies in other parts of the empire would not be alerted to upcoming hostile actions. All of these desires could only be satisfied if the whole Roman world was using one calendar.

As noted in my previous post My Thoughts One Week into 2021, Caesar honored the Roman God Janus by officially “naming” January as the year’s opening month.

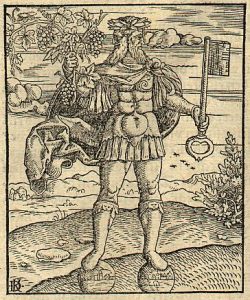

This designation by Caesar gave a formal stamp of approval to a tradition that was at least one century old by 46BC. Janus was the Roman god of transitions. His presence and blessings were sought at every ceremony of opening or transition.

Janus is a form of the Latin word ianua, which means door or gate. Janus was the janitor. He was the doorkeeper or guard of the gate.

The Julian calendar ruled supreme for more than 1600 years. However, the Julian calendar had a problem. It was too long. By the late 16th century, the ecclesiastical calendar and feast were more than a week out of sync with the solar solstices and equinoxes.

To fix this problem, Pope Gregory XIII issued his papal bull Inter Gravissimas in 1582, announcing calendar reforms for all of Catholic Christendom.

To make the holy days line up with the solar dates, Gregory ordered the Christian world to “eliminate” 10 days. In October 1582, the Gregorian calendar skipped the dates of the 5th through the 14th. Thursday, October 4, 1582, was followed by Friday, October 15, 1582. Most of the world didn’t understand what was going on. People thought that they had lost 10 days.

England had already rejected the Catholic Church’s claim over their religious lives and formed the Church of England. So they rejected Gregory’s calendar as a grand overreach into their civil and religious sovereignty. However, by 1750 England and the American colonies saw the need for a revised calendar. In the 1750s, most of the English speaking world accepted a variation of the Gregorian calendar. By 1750, they had to eliminate 11 days to make the calendar agree with the solar dates.

The newly revised Gregorian calendar is still too long. It is 26 seconds longer than the solar year. Thus, by the year 5,000, we will need to drop a day from the calendar again. Although I am curious about how the calendar will be adjusted, I am confident that I won’t be here to worry about it.

In my next post, I will turn my attention to another topic. On Sunday, January 17, I was the guest speaker at a church service. During the preceding week, our senior pastor, who had been scheduled to speak on Sunday, came down with the flu (not covid). Our assistant pastor was in the hospital recuperating from open-heart surgery to repair four blockages. Our youth pastor had been out of town all week at a youth camp. So I got a call on Thursday asking if I could fill in. Since it had been more than a decade since I last did any pulpit supply work, I was excited and apprehensive at the same time. I said, “Yes!” Since the message is too long for one post, I now have several posts that I will be publishing over the next couple of weeks. The title of the lesson is Four Chairs. It looks at where we sit in relationship to the cross.