In my most recent post A New Millennium – The Same Old Story, Part I, I introduced ten disturbances that rocked the world of American Higher Education in the 21st century. I concluded that post with the indication that my next post would continue the story with additional troubles, calamities, cataclysms, emergencies, and disasters. Here are ten more. In reality, I feel that the twenty features that I selected to spotlight in my two posts only touch the surface of the current problems plaguing American Higher Education. However, they definitely indicate the breadth and depth of the difficulties facing American Higher Education.

In this post, I will follow the pattern as my previous one. I begin with a short explanation of the problem, followed by an example of a commentator or the media’s interpretation of the crisis. The list is again in chronological order according to the publication date of the article that I reference.

- In 2003, Derek Bok offered a groundbreaking look at the Commercialization of Higher Education in his visionary book Universities in the Marketplace: The Commercialization of Higher Education. This tour de force asks the question: “Is everything in a university for sale if the price is right?” Bok’s answer is that the answer is too often “yes.” In today’s economy, Bok suggests that too many American universities are attempting to profit financially not only from athletics but also from those areas that touch the heart of the academy, research, and educational content.

- The April 2007 Inside Higher Ed Opinion Second Thoughts About Professionalism by Jeffrey Ross paints a dark and menacing picture of the Professionalization of Education, particularly at the community college level. The first sentence of the article by Ross screams skepticism: “I’m not sure what is meant by professionalism. I suppose it has something to do with knowing what you are supposed to know on the job.” Is Ross talking about students and their education or the faculty and administrators leading our community colleges? It’s not until his fourth paragraph that he finally states “I sense that professionalism at the community college has to do with a code of behavior, a belief system, which defines how instructors and administrators should act.” Here’s where Ross and professionalism part company. He admits that “the current educator-as-professional movement…has created a somewhat misfit work culture for educators…” To describe what’s wrong with the community college culture he invokes an 18th century Jonathan Swift metaphor: “Like the learned scientists at the grand Academy of Lagado in Gulliver’s Voyages, we are focused and employed. So focused we can’t be distracted–even by the day-to-day realities of those persons whose intellectual needs we are employed to meet. So many valuable student interactions displaced by urgent meetings!” Ross calls for a new voice to speak for and lead the community college community.

- The concept of Academic Freedom is considered one of the foundational principles of modern academe. The origin of academic freedom can be traced back to at least 399 B.C. when Socrates defended himself at his trial before 500 fellow Athenians against a charge of impiety and corruption of youth. He vigorously argued that the gods had bestowed on him the freedom to think. With this freedom, he was entrusted with the responsibility of the freedom to teach his thoughts. It was a duty he owed to the gods and a benefit he must confer upon the state. This idea has never been universally accepted. Socrates was found guilty and sentenced to death. The next appearance of academic freedom must wait until the 12th century when Frederick I Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, issued the writ Privilegium Scholasticum. One of its provisions protected faculty and students in their pursuit of knowledge from the intrusions of all political authorities. However, instead of creating a safe harbor for faculty and students within the halls of the University of Bologna, it fermented strife and turmoil amongst them and the Roman Catholic Church. The battles lasted for two centuries until the University formally established a School of Theology. For the next five centuries, the Church was a dominant force in the life of the University. For the first several centuries of higher education in the United States, many colleges were controlled by religious thought which limited what could be taught. In 1940 philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell was denied a professorial position at the City University of New York because he was “morally unfit.” This charge was primarily due to his public views on extra-marital sex, marriage, divorce, and birth control. As soon as the announcement of his appointment to the CUNY faculty became public, William Manning, a bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church, sent a letter to the New York Times denouncing Russell as a recognized propagandist against both religion and morality. The Board withdrew its offer and the city withdrew funding for the faculty position. in 1988 Les Csorba of Accuracy in Academia claimed, “academic freedom on college campuses is nothing more than a useful device which gives license to some people and silences others”. In a December 2010 article Defining Academic Freedom in Inside Higher Ed, Cary Nelson, President of the American Association of University Professors, attempted to clear up confusion about academic freedom. He outlined a dozen points of What it does do and a dozen points of What it doesn’t do. In spite of Nelson’s article, arguments about academic freedom constantly rage both on and off campuses.

- Public Support for Higher Education Is Shrinking. Tell us something we don’t already know! Since 1980 state and local financial support of higher education has dramatically decreased in multiple ways. This shrinkage is happening both in terms of real dollars and the share of support received by public colleges and universities. In a Winter 2012 report State Funding: A Race to the Bottom from the American Council on Education, Thomas Mortenson claims that if states do not change their funding patterns, by 2059, they will not be providing any support for higher education. In 2010, state and local governments spent $103.7B. This was 34.1 percent of all expenditures in the United States on higher education. This was down from its 1975 peak of 60.3 percent. Since the tax revolts of 1980, only two states, Wyoming (+2.3 percent) and North Dakota (+0.8 percent), have increased their share of higher education expenditures. Declining state support for higher education leads directly to tuition increases and a greater financial burden on students for the cost of their education.

- We’ve known for years that the Cost of Regulatory Compliance is significant, but there was no real attempt to calculate it until 2014. In early 2014, Vanderbilt University’s Chancellor Nicholas Zeppos commissioned a study by the Boston Consulting Group to determine how much colleges and universities were spending to comply with federal regulations. On October 19, 2015, Melanie Moran published her preliminary summary of the results, Study estimates cost of regulatory compliance at 13 colleges and universities, online in Vanderbilt News. These results were the shot heard all around American higher education. Two of the most significant conclusions indicated that regulatory compliance represented 3 to 11 percent of higher education institutions’ nonhospital operating expenses, and that faculty and staff spend 4 to 15 percent of their time complying with federal regulations. The reaction was swift and nearly unanimous: “…compliance with federal regulations results in a significant direct and indirect financial cost.” I was not surprised by the study’s findings. In the early 1980’s I was a one-person Institutional Research Office at a small liberal arts college. I did an inventory of all the reports that we were required to complete and submit each year for various federal, state, athletic oversight groups, and accreditation agencies. There were more than 90 required annual reports. In addition to those compliance reports, I also added up the number of requests for data from outside organizations such as the Council for the Advancement of Small Colleges (CASC), American Association for University Professors (AAUP), Christian College Coalition (CCC), North American Council for Christian Admissions Professionals (NACCAP), The College Board, American College Testing (ACT), American Associations of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO), National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), Association of Institutional Research (AIR), American Association for Higher Education (AAHE), Association of Governing Boards (AGB), and the American Council on Education (ACE). There were more than 100 such annual requests for data. The third group of reports handled by my office was data requests from advertisers such as Peterson’s Guides and Campus Life Magazine which publicized comparisons of colleges. If you didn’t comply with their data requests, they used data they “gathered” from various sources such as IPEDS and College Board. However, the institution had no control over how they interpreted or misinterpreted that data. There were at least ten such requests each year. Thus for a small college enrolling less than 800 students, to stay in “good standing” with governmental and accrediting agencies, the higher education community, and the general public, we were compelled to complete and submit more than 200 annual reports. Each of these reports easily averaged more than 10 hours of my time to verify and justify the consistency of the data. If you included the time of various offices required to compile the data, you are talking about another 20 hours each. This adds up to more than 6,000 hours of faculty, staff or administrators time per year. This is the equivalent of more than 3 full-time employees per year to handle unfunded “mandates.” Fortunately, this college was in the Middle States accrediting region. The “joke” among institutional research professionals in the early 1980s was that the proscribed accrediting and reporting requirements of the Southern Association of Schools and Colleges (SACS) were the “institutional researchers full-employment act.”

- A matter of profound concern to many in American higher education for more than four decades is the Rise and Fall of Proprietary Higher Education. Prior to 1976 proprietary higher education was hardly a blip on the radar screens of higher education. That began to change in 1976 when John Sperling and John Murphy founded The University of Pheonix (UoP). The first class consisted of only eight students. By 1986 the enrollment had grown to more than 6,000. In 1994 Sperling took The Apollo Group public. By 2000 the enrollment was over 100,000 and growing by 25% per year. By 2010 proprietary institutions enrolled more than 2 million, 12 percent of all post-secondary students. Everything seemed to be coming up roses. The article The Rise and Fall of For-Profit Schools by James Surowiecki which appeared in the November 2, 2015 issue of THE NEW YORKER magazine paints a different picture. In those five years, UoP enrollment was cut in half. The Department of Defense removed it from its approved list for tuition payments for active duty troops. Regulatory agencies began investigating the recruitment and financial aid practices of proprietary institutions. The federal government looked closely at job-placement claims and ability of graduates to repay student loans. Proprietary institutions are now required to prove that on average, students’ loan payments will not exceed eight percent of their expected annual income. Schools that fail this test four years in a row will have their access to federal loans cut off. The implementation of this rule has effectively put a significant number of such schools out of business.

- The evidence and data are clear. There are Gender and Racial Disparities, Bias, and Discrimination Within the Academy. Unfortunately, these attitudes and behaviors have been present as long as higher education has existed. More unfortunately, for many centuries, they were accepted as the norm. However, that is no longer the case. Over the past half century, there have been many small and some large steps to expose and fix these problems. In the 21st century, the pace of restructuring higher education has increased. In the case of gender disparities, a complicated paradox has emerged. One part of that paradox is illustrated in Caroline Simon’s March 8, 2017, USA Today article There’s a double gender gap in higher education–and here’s why. Simon discusses the lack of women in top leadership positions in higher education and the fact that women earn less than men in similar positions. This discrepancy at the top is in stark contrast to the fact that since 1970, the number of women students and graduates have outpaced the number of men. With more women college graduates, the question is raised about the number of women in faculty and administrative positions. There are more men at the higher faculty ranks than women, even though there are more women at the lowest faculty ranks than men. When we add in the racial component, the contrasts are much more complicated.

- A July 2017 Fortune Media commentary This Economic Bubble Is Going to Wreak Havoc When It Bursts on higher education by Jim Rogers and Robert Craig Baum highlights the economic distress that the Student Debt Bubble could cause individual higher education borrowers, American higher education, and the United States economy as a whole. Rogers and Baum begin their commentary with the claim that “An imminent economic crisis the likes of which this generation has never experienced is coming…The higher education bubble (one-sixth of the U.S. economy) will likely burst with the force of all precious catastrophes combined–a shock wave so sudden, so large, that it gathers the full force of the savings and loan, insurance, energy, tech, and mortgage crashes, creating a blockbuster-level perfect storm.” They paint a grim picture of the future of AHE, suggesting that AHE leaders have no grasp of economic reality.

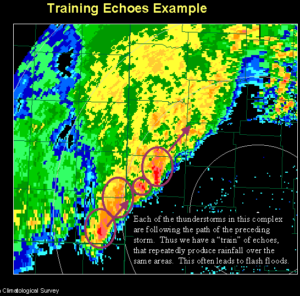

- Natural and Man-Made Disasters Leave Indelible Effects on Colleges and Universities. Every year since 2000 there has been at least one catastrophic event that had devastating effects on American colleges, universities, and their associated personnel. However, some stand out far beyond most. In 2017, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria pounded the island of Puerto Rica and the United States mainland. The August 28, 2018 Chronicle of Higher Education article Disaster-Stricken Colleges Will Get $63 Million in Aid From the Education Dept. by Fernanda Zamudio-Suaréz and Lindsay Ellis spotlights the U.S. Department of Education response to the resultant damage to 47 American colleges and universities. Most of the Puerto Rican institutions lost an entire year of operations in addition to the physical damage to their buildings. None of them have fully recovered their enrollments since their students and faculty scattered all over the United States. Also fresh in our memories are the western U.S. wildfires of 2017 and 2018 which affected many colleges in California and other western states. Other hurricanes, namely Katrina (2005) and Sandy (2012), caused significant damage to colleges and universities. I would also dare say that everyone in American higher education remembers where they were on the morning of September 11, 2001. The world watched in utter disbelief the tragic events of that day as the terrorists attacked the World Trade Center in New York City. Some colleges in New York were directly affected, while many in neighboring states were indirectly affected. In every year of the 21st century, some catastrophic event has affected one or more American college or university.

- Jeff Selingo in his September 2018 article How the Great Recession Changed Higher Education Forever in The Washington Post recounts the Lasting Effect of the Great Recession of 2008 on American Higher Education. The waves of troubled financial waters which swept across the world almost swamped American Higher Education. A number of institutions sank, drowning many students and faculty. Many of the institutions which survived attempted to lure the dwindling supply of students through their doors with a “fire sale” and huge tuition discounts. For many students the primary reason they went to college changed. Since 2008, students now see college as a means to secure better jobs, rather than a source of general education in order to be more human. This has meant an uptick in the “practical majors” such as business and health care, and a significant downturn in the humanities. A third and more subtle change occurred at the presidential and board level of colleges. Their focus shifted to more short-term survival interests, rather than long-term sustainability issues. History predicts that there will be more economic downturns in the future. However, this time American colleges and universities are less prepared to deal with these periods of famine.

WHEW! The deeper I dug into the current difficulties and issues facing American higher education, the more problems I found, and the more complicated they became. Having done a number of extensive home remodeling or rehabilitation jobs as we moved around the country chasing new academic administrative positions, without any qualms I can say that American higher education is like a DIY money-pit. The job will always cost more than you budgeted and take longer than you first estimated. Another parallelism between American higher education concerns and DIY projects are hidden issues. When you remove a wall you are never sure what you will find beneath the plaster or the drywall. Even when you have blueprints of the house, you don’t know whether someone made previous alterations that were not documented. Are there hidden pipes and wires that will be extremely difficult to redirect? Is there mold or asbestos just waiting to catch you? Is that a load-bearing wall you want to tear out because you think it is unnecessary or undesirable? If that wall was designed to do a specific job and you don’t compensate for its removal, you run the risk of collapsing the whole building.

Although I have found more than 10 additional problems in American higher education on which I could focus, I have decided to turn my attention to the 20 that I have already highlighted. I think you have gotten the point: American Higher Education is a Mess. My next post will look at the issue of the Adjunctification of the Faculty.