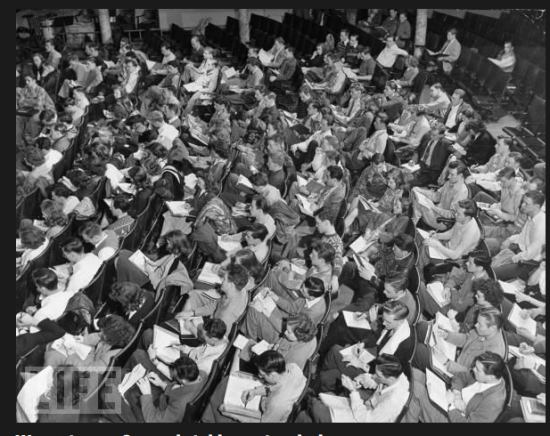

I began this series of posts on Education’s Big Lie more than three months ago with the post Education’s Big Lie, Part I – Introduction. In attempting to make my first point I highlighted Procrustian’s aphorism “one size fits all.”

To address the question of whether the American systems of elementary, secondary and higher education are forgetting or ignoring students, I turn now to Henry David Thoreau, Albert Einstein, and Lyndon Johnson. This extremely disparate group of individuals might seem to be an unusual choice of spokespersons.

Thoreau was a 19th-century American writer and transcendental thinker. He is probably most well-known for his book “Walden; or, Life in the Woods“, a treatise on the simple life and self-sufficiency. The key tenets of transcendentalism included the inherent goodness of nature and individuals. Followers of this world view believed that our culture, society and its institutions had corrupted the purity with which each of us was born. To return to our best, natural state, we should withdraw from society.

Thoreau is reported to have made the following comment concerning a child’s potential:

Do you know what you are? You are a marvel. You are unique. In all the years that have passed, there has never been another child like you. Your legs, your arms, your clever fingers, the way you move. You may become a Shakespeare, a Michelangelo, a Beethoven. You have the capacity for anything.

I picked Thoreau because he could see the future in the eyes of a child playing with a jar of paint. Most people only see the child making a mess. To Thoreau, that child was envisioning a masterpiece on the epic scale of the Sistine Chapel.

In December 1999, Time Magazine named Albert Einstein the Person of the Century. The editors proclaimed him to be a “genius, political refugee, humanitarian, locksmith of the mysteries of the atom and the universe.” They further explained their somewhat controversial choice by saying, “He was the pre-eminent scientist in a century dominated by science. The touchstones of the era–the Bomb, the Big Bang, quantum physics and electronics–all bear his imprint.”

Einstein often spoke of the importance and significance of the individual. The following quote is generally attributed to him: manner:

The person who follows the crowd will usually go no further than the crowd. The person who walks alone is likely to find himself in places no one has ever seen before.

I picked Einstein and this quote denigrating the process of following the masses because Einstein was a person who set out on his own most of his life. He separated himself from the crowd and concentrated his attention on what he saw, heard and thought. These were things that people who took the shoveled path never saw.

Lyndon Johnson was elected Vice President of the United States in 1960 when John Kennedy won the presidency over Richard Nixon. When Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Johnson became the 36th President of the United States. Under Johnson’s leadership, a series of domestic legislative programs called the Great Society and the War on Poverty were enacted. They included Medicare and Medicaid, and a significant increase in federal spending on education, the arts, urban and rural development, and public services. There was also a dramatic increase in governmental attention to the civil rights of individuals.

In President’s Johnson prepared remarks he said,

By passing this bill, we bridge the gap between helplessness and hope for more than five million educationally deprived children.

We put into the hands of our youth more than 30 million new books, and into many of our schools their first libraries.

We reduce the terrible time lag in bringing new teaching techniques into the nation’s classrooms.

We strengthen state and local agencies which bear the burden and the challenge of better education.

And we rekindle the revolution–the revolution of the spirit against the tyranny of ignorance.

As a son of a tenant farmer, I know that education is the only valid passport from poverty.

As a former teacher–and, I hope, a future one–I have great expectations of what this law will mean for all of our young people.

As President of the United States, I believe deeply no law I have signed or will ever sign means more to the future of America.

To each and everyone who contributed to this day, the nation is indebted.

What an awesome responsibility to place on one law:

- Bridge the gap between helplessness and hope

- Put new books and libraries in our nation’s schools

- Reduce the time lag in bringing new teaching techniques into our classrooms

- Rekindle the revolution against the tyranny of ignorance

- Provide a valid passport from poverty

- Give young people great expectations for their futures

In the half a century since ESEA was signed into law, there have been a few victories. One of the first to occur in the late 1960’s was the concept of magnet schools. These schools were introduced as an educational reform model of public school choice as a way to address educational inequity. Magnet schools are based on the premise that students do not learn in the same way or at the same rate; that if we find a unifying theme or a different organizational structure for students of similar interest, students will learn more in all areas. In other words, if a magnet school voluntarily attracts students and teachers, it will succeed because, more than for any other reason, those in attendance want to be there. They will have chosen that school. These schools usually have superior facilities and staff and offer a specialized curriculum designed to attract pupils from any school throughout a city or district. Magnet schools have been created centered around STEM fields, the arts, and the classics.

A number of school districts have been very successful at putting new books and new technologies into libraries and the hands of our students. For example, the Port Charlotte school district on the Gulf Coast of Florida, approximately half way between Sarasota and Fort Myers, has a new combination library and media center that rivals many college facilities in its equipment and attractiveness. Its mission reflects the goals of President Johnson and the EASA legislation.

The Mission of the Port Charlotte High School Media Center is to encourage our students to develop a love of reading, to appreciate the many kinds of literature available, and to ensure that students become effective users of ideas and information. We aim to provide a comprehensive program of service, print and non-print materials, equipment and technology that will help meet the students’ academic and leisure needs. Our resources and instruction support the educational goals of Port Charlotte High School.

Before we get too excited and get the idea that most public school libraries look like this, we must take note that Port Charlotte is a wealthy suburban district where the median price of homes in mid-2017 is over $235,000. It was ranked as the 15th best public school district in Florida by NICHE, a small firm that is comprised of data scientists, engineers, and parents, who are passionate about helping people discover the schools and neighborhoods that are right for them and their children. The total 2016 fiscal year budget for the Port Charlotte School District was $247million, of which $30million was appropriated for capital improvement projects.

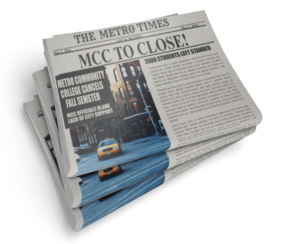

There are many other successful school districts across the United States. However, the failures have far outnumbered the successes. To find examples of these failures, all one has to do is read the daily or weekly news reports coming out of Washington and many other cities and towns around the United States. In my next post, I will highlight some of those failures. Having been a participant in and observer of education for more than 65 years, I have seen at least six types of students who have been and are being ignored by American public K-12 education as a system and by individual teachers within the system. In subsequent posts, I will highlight these types of students and make some suggestions concerning what I believe needs to be done to bring these students into the mainstream.