In the most recent post of this series, Broken Model of American Higher Education, Part VI: Incremental Growth Will Not Be Enough, I left American Higher Education (AHE) hanging on the edge of a cliff by its fingernails. In that post, I claimed that American higher education will need exponential growth to meet the demands and expectations of those in the economic, political and higher education arenas, as well as the American general public.

I also implied that historically, exponential growth has only occurred in American higher education as a result of disruptive actions, either on the national or international stage. In other words, exponential growth hasn’t occurred naturally. It has required a little help from our friends (or enemies).

As I continue to fight off the remnants of a battle with mild aphasia, I was using the word disruption in a positive way. My initial reaction was that the word disruption wasn’t necessarily a negative term. Thus, in my mind, I was having a full-fledged battle over the idea that disruptive innovations were automatically bad. I was envisioning a number of positive results from the numerous discontinuities that I saw coming. From what I could remember, I thought disruption was a term that just meant a break in a continuum. However, as I researched the word I found that it has a much darker and more violent past. The word is derived from the compound Latin word, disrumpere, which comes from the Latin prefix dis- which means “apart” and the Latin verb rumpere which means “to forcefully break.” Thus, the word disruption implies an emphatic, hostile action on the part of someone or something. Therefore, I will admit that labeling something as a disruptive innovation is tantamount to throwing it under a bus or on a trash pile of junk.

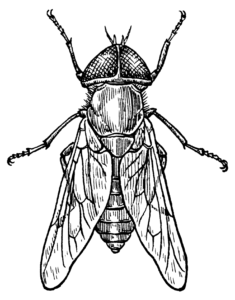

With that background, I am beginning to see why the word disruption has recently engendered as much negative press in higher education and political circles as it has. In higher education and political circles, disruptions are seen as major threats to the status quo. When you are part of the status quo, disruptions are particularly annoying and bothersome. Throughout history, disruptive individuals have been compared to gadflies, those persistent, irritating insects that rove around biting humans and farm animals, stinging sharply, sucking blood and transmitting diseases to their victims.

One of the earliest written reference to gadfly may be the prophet Jeremiah. In Jeremiah 46:20 in the King James Version, we read “Egypt is like a very fair heifer, but destruction cometh; it cometh out of the north.” Where is the gadfly in this verse? In the New International Version (NIV), this verse reads “Egypt is a beautiful heifer, but a gadfly is coming against her from the north.” The Hebrew word : קֶ֫רֶץ , transliterated as qarats, which is translated as destruction in the KJV, occurs only this one time in the Bible. Somewhat surprisingly, the KJV does use the verb gad one time. It is in Jeremiah 2:36, as part of the word of rebuke that the Lord had given Jeremiah for the people of Israel. Jeremiah asks the Israelites, “Why gaddest thou about so much to change thy way? thou also shalt be ashamed of Egypt, as thou wast ashamed of Assyria.“ However, the English translation “gaddest about so much to change thy way” is really לְשַׁנּ֣וֹת מְאֹ֖ד תֵּזְלִ֥י in Hebrew. The transliteration lə·šan·nō·wṯ mə·’ōḏ tê·zə·lî literally means “you go about so much changing your ways.” Thus, this reference is is not directed at the gadfly, whose sole purpose is to cause problems. It refers to an individual who roams from place to place in an irresponsible manner, without a fixed physical or ethical mooring.

From non Biblical sources, in addition to the connotation of extermination or utter destruction, qarats may also be translated as nipping or biting, hence the translation “gadfly.” Another ancient reference to the gadfly occurs in Plato’s Apology where Socrates describes himself as a social gadfly that flies around and stings the lazy horse that is Athens. Socrates was trying to speed up the stalled change that he thought was absolutely necessary if Athens was to maintain its place as a world leader. Where is the modern day Socrates, prodding the seemingly intractable American higher education into action so that it can maintain its place as a world leader? Does the above make those of us who are saying that American higher education must change if it is to maintain its place as a world leader and the agent of social improvement into gadflies? If so, I am ready to accept that mantle.

In some circles within American higher education the concept of disruptive innovation has almost become synonymous with the picture of the heinous, atrocious, and monstrous and despicable leper who must be banished from the clean society of tradition-bound higher education. In Ancient Israel, lepers were required to warn “clean citizens” of their presence and the danger that they represented. Lepers were isolated from clean society so as not to infect the general population with this insidious condition. In the 17th Century woodcut below depicting the cleansing of the ten lepers by Christ, the lepers are shown with warning clappers, letting everyone know that they were unclean. Were these clappers the precursors to today’s trigger warnings, which many in educational circles find aggravating and totally unnecessary?

In a number of recent conversations I have complained bitterly to friends that society and culture are pulling words “right out from under my feet.” I thought that disruption was going to be an excellent example. However, I was mistaken and I must apologize to those friends with whom I argued. It wasn’t society that was changing or evolving the definition of words. My mind was playing tricks on me. If I can’t use the word disruption, what term can I use? My search for a replacement has been arduous and without much success. The best alternative that I have so far is discontinuity. So instead of disruptive innovations, going forward I will talk and write about discontinuous innovations. However, I am not completely satisfied with this choice. It almost sound superfluous and doesn’t have the ring of disruptive innovations. Readers, do you have any suggestions?

In looking at the history of American higher education, what were the innovations or events that created discontinuities in the fabric of American higher education? When the United States federal government instituted land grant colleges in the last half of the 19th century, that created a huge discontinuity in traditional, liberal arts education. When the unemployment rate in the United States shot up from less than 5% in 1928 to more than 20% in the early 1930s, that was another discontinuity. When the United States entered World War II, that caused another tear in the continuum of American higher education. When more than 10 million soldiers returned to civilian life after World War II, looking for jobs, that was a discontinuity. The G.I. Bill providing them the wherewithal to go to college was an innovation that created a huge discontinuity that had lasting effects for years.

Are there pedological changes and technological advances that will challenge the stubborn fabric of American higher education? The rise of the for-profit educational sector, online education, and andragogy have opened the eyes of a large segment of Americans, seemingly forgotten by traditional American higher education, the non-traditional students which are in dire need of education. It has created a pented up demand for educational opportunities previously unavailable and seemingly withheld from these individuals. This has opened the door for another possible huge discontinuity in American higher education.

The Barnes & Noble College report Achieving Success for Non-Traditional Students: Exploring the Changing Face of Today’s Student Population predicts that between 2016 and 2022, there will be an 8.7% growth in traditional students, but a 21.7% growth in non-traditional students. The report goes on to suggest that non-traditional students are two times more likely to prefer on-line courses over the face-to-face courses preferred by traditional students.

The Barnes & Noble (B&N) study defined at risk students as students who met at least one of three conditions. The conditions were: 1) a low sense of connection to the school; 2) low confidence of completing the program; and 3) negative feelings about current situations at school. The B&N study found that 29% of current (2015) non-traditional students were at risk while only 17% of traditional students were at risk. This difference was statistically significant.

The B&N Study also suggested that schools could maximize their effectiveness in helping all students complete programs if they would address six key challenges. These challenges were: 1) know your “at-risk” students;” 2) increase access to affordable materials/learning solutions; 3) offer expanded career counseling support; 4) offer services that will help students deal with their stresses; 5) act as their support system and help engage more deeply; and 6) provide clear, proactive communication and information about the support services offered. All of these challenges make eminent sense. Schools that best mitigate the challenges of at risk students will help more of them complete programs.

The one startling fact that I found missing from the B&N report was any reporting of the current rates of success of students completing programs. From studies by the American Council on Education (ACE) and the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES), we know that the national average of traditional students completing programs is about 55%; while the average completion percentage for non-traditional students is about 33%. If B&N found 17% of traditional students and 29% of non-traditional students were at risk, but we know that at least 45% and 67%, respectively, are not completing programs, why weren’t there 28% more traditional students and 38% more non-traditional students at risk? I would suggest that there are at least this many more current traditional and non-traditional students who are at risk. The difficulty is that we don’t know how to identify them. If we can’t identify them, we certainly can’t help them.

However, identifying these obvious candidates for improving the educational picture in America will not necessarily be the panacea to solving all of our problems. The University of California system of higher education is a prime example of more of the problems within American higher education. The California system says that it is overloaded. With current facilities and staffing, the system claims that it can’t adequately serve the students that it now has. If we have more students completing programs, where will we “teach” these students and who will teach them? If the system doesn’t have the funds to hire more teachers or build more classrooms, where will the state or institutions get that money? I have already offered my take on the idea of how acceptable raising tuition will be with prospective students and those responsible for the tuition bills of these students.

If you are within higher education, be prepared for the coming discontinuities. You may even have to be prepared for disruptions. Without changes, we can’t and will not meet the coming demands and expectations.