This is the first of several follow-up posts to the posts What does higher education have in common with the watch industry, the chocolate industry and toilet paper manufacturers? and Comparison of American Higher Education with the American Automotive Industry that I published six years ago. I have been thinking about reprising the idea after seeing the YouTube video, HoboTraveler.com The AskAndy Show, about toilet paper with no center core. Although Kimberly-Clarke introduced the “Natural Roll” under the Scott Brand name about 8 years ago with much fanfare as to how it was going to reduce landfill, incinerator and recycling waste in the United States, it seems to be a colossal flop here, but it has caught on in Europe and Asia. Witness the following U.K. news article from 2014, Roll with the times: U.S. company takes the cardboard OUT of toilet paper for first time in a century in move to cut down on waste.

In the initial roll-out of the tubeless toilet paper, Kimberley-Clarke indicated that approximately 17 billion rolls are used world-wide, each year. That would be enough to fill the Empire State Building twice. Placed end-to-end, this many rolls would stretch around the Earth at the equator 40 times. They also represent 160 million pounds of waste, roughly equal to the weight of 250 Boeing 747s. In an effort to encourage the use of the core-less toilet paper rolls, ScottBrand has published the following website for consumers to estimate how many rolls their families would typically use: How many tubes do you use?

Why would the core-less roll find a burgeoning market in Europe and Asia, but not in the U.S.? There is probably no one answer. Most likely, it is a combination of a number of factors. Most US consumers give lip service to going “green.” However, if it costs more or is a little less convenient, the US consumer seems to stick to the old way of doing things. Consider recent pushes for light bulb, battery and electronic equipment recycling. In Asia and Europe, particularly Eastern Europe, consumer products are far more controled by central government decisions.

What’s all this have to do with higher education? Let’s go back to the 1890s when toilet paper rolls were introduced. Toilet paper rolls were a new convenient way to provide a sanitary way for people to clean themselves after the elimination of bodily waste. They didn’t catch on right away. Their use skyrocketed with the almost universal introduction of indoor plumbing, community sewer systems, and private septic systems that were built on the premise of the disposal of only biodegradable products.

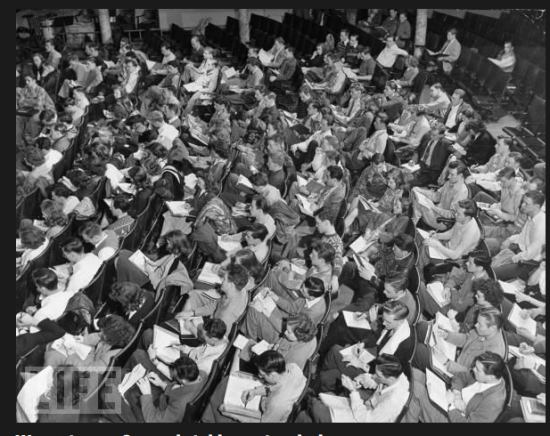

Prior to the return of soldiers from World War II and the introduction of the educational benefits contained in the G.I. Bill (or Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944), American colleges could be divided into three models. The first model was the small, quintessential residential liberal arts college. The second model was the land grant college that grew out of the 1862 and 1890 Morrill Acts. These IHEs tended to be larger schools that emphasized agricultural education and research, and community service outreach programming. The third model was born out of the European research-based educational institutions that began in the US, around the turn of the 20th century, with the flourishing of the Ivy League institutions and the birth and growth of the University of Chicago and Stanford University. With millions of servicemen and women looking for educational opportunities in the latter half of the 1940s and the first half of the 1950s, the existing IHEs didn’t have the capacity to handle such a load.

One very surprising solution to this overcrowding was the unexpected growth of for-profit institutions in the late 1940’s. Many of these institutions were labeled “fly-by-night” schools at the time. Sound familiar? There was a two pronged approach to tackling the problems created by these schools. The first was to increase restrictions by the federal government and accrediting agencies. Sound familiar, again? The second was the unprecedented expansion in the latter half of the 20th century of existing traditional colleges and universities in terms of enrollments, programs and facilities. These expansions created a secondary market demand for an increased number of faculty, which further drove the expansion of graduate programs. Since the early 1990s, the job prospects, in and out of academia, of recent doctoral graduates in almost all disciplines have tanked. In many disciplines we now have a surplus of PhDs. What are we going to do with all of them?

As all of this has been happening, there has been call after call for more education. Politician after politician has pushed for more college graduates to meet the unmet demand for qualified job applicants. To meet these demands, American society has turned to three sources. The first has been for-profit institutions, that many accuse of operating unethically. Sound familiar? The second source is an explosion of non-traditional programs emanating from the traditional IHEs. If you can’t beat them, you might as well join them. The number of traditional IHEs with “adult educational programming,” online programs and even MOOCs has exploded. The third has been pressure from multiple sources on the traditional IHEs to be “more efficient” in their traditional programming. Everyone has THE SOLUTION.

However, when we try to partially implement these solutions, the situation seems to get worse. Enrollment in higher education has reached an all-time high. However, so has the number of attriters who enrolled in programs but don’t complete them. The level of borrowing for education has reached all-time highs, as has the number of defaults. As more under-prepared students have enrolled, accusations of dumbing down the curriculum have escalated.

What lesson can we learn from the toilet paper industry? Once American society has become accustomed to a particular approach to a particular problem, it is very difficult to move it to try something new. It makes no difference that the new product or service may be less expensive in the long run, and a better use of natural resources. It takes overwhelming pressure to introduce a new behavior and have it take hold a significant segment of society.

For those of us who are old enough to remember the early days of cable television, we can’t forget the overwhelming pressure from the ubiquitous MTV ads that shattered our ear drums with the droll, repetitive chant “I Want My MTV!!!” MTV hooked the adolescent crowd with a constant barrage of their ads and free introductory offers of music videos . For those of us who were somewhat beyond the adolescent years, we had athletically inclined ESPN, the first 24-hour sports and entertainment network. Fortunately, there was more sports than entertainment. Who can forget camel races, ostrich races and Australian rules football? Once the American public was hooked, ESPN is now a staple on all cable and satellite systems, usually with multiple channels. What’s the secret? Start early and small with a product that people want, then keep feeding them the candy to get them addicted.

For those of us who are old enough to remember the early days of cable television, we can’t forget the overwhelming pressure from the ubiquitous MTV ads that shattered our ear drums with the droll, repetitive chant “I Want My MTV!!!” MTV hooked the adolescent crowd with a constant barrage of their ads and free introductory offers of music videos . For those of us who were somewhat beyond the adolescent years, we had athletically inclined ESPN, the first 24-hour sports and entertainment network. Fortunately, there was more sports than entertainment. Who can forget camel races, ostrich races and Australian rules football? Once the American public was hooked, ESPN is now a staple on all cable and satellite systems, usually with multiple channels. What’s the secret? Start early and small with a product that people want, then keep feeding them the candy to get them addicted.

Is it too harsh to suggest that we need to get people addicted to education? We need to start hooking them on education early. Trying to get the late adolescent or an adult to see that they need education is too late. Talking to an early adolescent about the need to read can be like talking to a brick wall. We need to introduce children to books before they start schools. Kindergarten may be too late. This was the conclusion of the report STEM and Early Childhood — When Skills Take Root, commissioned by Mission: Readiness, a nonpartisan national security organization of more than 600 retired generals and admirals calling for smart investments in the upcoming generation of American children, and ReadyNation, an organization of more than 1400 business leaders who work together to strengthen American business through effective policies for children and youth. If we were to follow the recommendations of “When Skills Take Root” it would mean that parents would be responsible for introducing books and learning to their children at pre-K ages. That’s a tall order in this society, when many adults have not read a book in years.

Trying to get the late adolescent or an adult interested in educational programming that forgot them years ago is nonsensical. Attempting to lure a late adolescent or adult into academic programming that uses approaches that they rejected years ago is a nonstarter. We need to go where they live and think like they think. We must bring the reticent adolescents and adults slowly into the light. We need to speak their language and use their media and methods as a starting place. I know this goes against grand educational traditions, It is NOT how we learned. That doesn’t matter. We are in a war for peoples’ minds and we need to use the most effective weapons. If we don’t have those weapons in our arsenal, we need to add them. I know that this doesn’t solve our immediate problems. However, I can almost guarantee that it will eventually bare fruit, both for the general public and for IHEs.

This next two paragraphs are probably the strongest statement that I have ever made about the future of higher education. We are engaged in a war. As in any war, there will be casualties. Some of the casualties will be civilians, while others will be educators. We will not educate every adolescent or adult in society. However, we have a responsibility to try to save and educate as many civilians as we can. Some we will lose because they refuse to help themselves. If individuals refuse to be educated, we can’t force it on them. Some we will lose because we don’t have the forces to reach them or we have deployed our assets incorrectly. We need to carefully study our battle plans to reach as many as we possibly can. We will lose some educators in the battle, because we haven’t trained, equipped, deployed or supported them properly. These loses are the most unfortunate because they could have been prevented.

We will also lose some IHEs along the way. We lost four within the past month with the announcements that St. Catharine College (KY), Dowling College (NY), Wright Career College (KS) and Burlington College (VT) will close their doors this summer and not offer classes this fall. Some IHEs will find themselves in untenable financial positions from which they can’t recover. The most unfortunate cases are probably those that we lose to friendly fire. If you are uncomfortable talking about the future of higher education in these terms, then I suggest that you might look for another profession. This war is only going to get messier. I am not a prophet of doom. Higher education will survive this onslaught and will regain some high ground. Will it recover all of its loses? It is possible, but not likely. However, the new emerging higher education will be different from the higher education of the late 20th century.

I began this post referring to a post in which I compared higher education to the watch, chocolate and toilet paper industries. In future posts, I will deal with the watch and chocolate industries. In the meantime, I would not recommend TPing anyone’s house or car.