My latest battle with the after effects of a series of taumatic brain incidents (ruptured blood vessel in a brain tumor, subsequent surgery to remove tumor, 4 tonic-clonic seizures) is a decline in my ability to think deductively, analytically, quantitatively or sequentially and a tendency to think about everything in terms of metaphors, analogies or pictures. In searching for something that I couldn’t find , I came across this video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DachRQNBGP8&feature=related that I believe expresses the real meaning of some very common words. I also don’t think that you have to live in a metaphoric world to appreciate its message. Grab a Kleenex box before watching it. Some of the pictures will make you laugh, others will make you cry. But that’s life.

Knowledge

Experience Is the Best Teacher of Patience and Wisdom

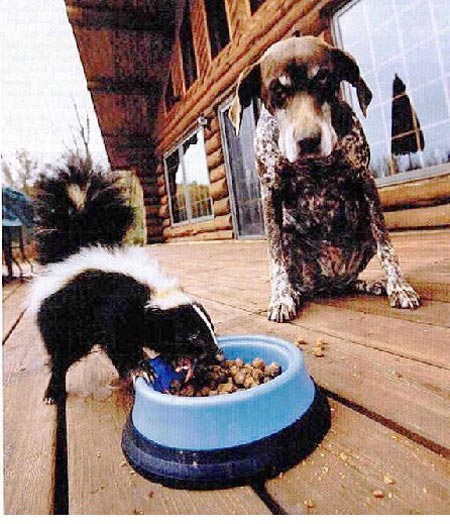

Two of the greatest virtues that humans can possess are patience and wisdom. The following photograph illustrates how the two virtues can be reluctantly brought together. Given the expression of utter frustration on the dog’s face, I am confident that the dog did not learn the patience and wisdom needed in this situation from a stint in obedience school. He knew that he had to give that skunk a wide berth and access to the food bowl. Most likely, he learned the lesson in the experiential school of hard knocks.

What’s the relationship among experience, wisdom and patience? Three quotes may help us.

1. By three methods, we may learn wisdom: fIrst by reflection, which is noblest; second by imitation; which is easiest; and third by experience which is the bitterest.” (Confucius)

The expression on the dog’s face reflects a very bitter experience. It certainly helped the dog learn the wisdom of not crossing a skunk.

2.“All human wisdom is summed up in two words: wait and hope.” (Alexandre Dumas).

Although the word patience is not present in the Dumas quote, the close synonym “wait” is front and center. Obviously in the picture, the dog is waiting for the skunk to finish its meal, and hoping that there will be some food left.

3. “Experience is not what happens to you; it’s what you do with what happens to you.” (Aldous Huxley)

Your experiences are not the events that swirl around you. They are the lessons that you learn and appropriate.

To summarize the importance of wisdom, let us go to one of the wisest individuals to ever live. Listen to King Solomon:

Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding. (Proverbs 4:7 KJV)

I was drawn to the above picture for two reasons. The first reason is my recent experiences with skunks. Since my TBI’s in 2009, I have only smelled the telltale aroma of a skunk once. I no longer “smell” skunks. I see skunks. This is one of my dysesthesia (cross-sensory perceptions). When the aroma of a skunk is in the air, it causes me to see the vision of a dead skunk on an unidentified road. This particular dysesthesia has its own advantage. It protects me from a very unpleasant odor.

The only time I smelled a skunk is another story. One day as my wife and I were riding in our car. I “really” saw a dead skunk along the side of the road. Suddenly, I smelled the pungent aroma. I exclaimed to my wife, “Well, what do you know, I smelled that skunk!” She hesitantly replied, “Honey, I’m sorry but there’s no skunk odor.” She continued by saying that she saw the dead skunk and was very surprised that there was no aroma emanating from it. So instead of ridding myself of this particular cross-sensory perception, I had picked up another hallucination. My memory of skunks had kicked in. The sight of the dead skunk triggered the repressed memory of a non-existent odor.

The second reason this picture fascinated me was the fact that it reminded me of the pet dog I had for 17 years, as I grew up. All he needed was one encounter with a skunk that he had when he was still a puppy. He never messed with one again. Experience was a great teacher, and my dog learned well. Although he was a small fox and rat terrier mix-breed, he was feisty and very jealous of his domain. He was accustomed to chasing any four-legged creature no matter how big or fierce that dared to venture into our yard, except skunks. It was funny watching him trying to herd the cows from our neighbor’s farm back into their own pasture. I often wish I had the foresight to capture the looks of shame and resignation on the faces of the cows as they slowly meandered back into their pasture, and the look of joyful victory on the face of my dog as he barked a couple of taunting “Goodbye and good riddance” from his side of the fence. He had proudly defended his territory again. He had no fear of huge cows, but he steered clear of skunks.

All of this reminded me of a quote about learning that is usually attributed to Mark Twain: “A man who carries a cat by the tail learns something he can learn in no other way.” Please believe, I am not advocating carrying a polecat by the tail unless you want to learn something you and anyone else who comes in contact with you with never forget. I may not be able to “really” smell a skunk now. However, I do remember what their odor smells like, and I do not wish to tempt my sensory perceptions that far.

General Education and Turf Wars

The National Endowment for the Humanities begin their booklet “50 Hours: A Core Curriculum for College Students” with a quote by Mark Van Doren from Liberal Education: “The one intolerable thing in education is the absence of ntellectual design.” I find this ironic in that the curriculum outlined in the booklet and the process used by most institutions to arrive at their general education is a process of turf wars. I find almost nothing intellectual in turf wars. In turf wars, the largest, most powerful departments will win almost every time.

I remember the process of redesigning the general education at one institution. At this institution the general education was listed as 48 hours. As we surveyed the faculty, it was their over-whelming conclusion that 48 hours was too large. Why? Because this didn’t give students enough room to complete a degree in many disciplines within the normal four-year path to a degree of 120 hours. How is this possible? Many majors specified courses in other disciplines as requirements within their discipline. When you counted these courses and the required prerequisites for these courses, the total number of required hours for the average major was well over 90 hours. For example, the psychology major required a course in statistics. But the mathematics department required a course in Fundamentals of Mathematics as a prerequisite for statistics which was different from the general education course that was entitled Quantitative Reasoning. Thus the typical psychology major had to take 9 hours of courses from the mathematics department. In another area, the psychology major required a two semester sequence in anatomy and physiology (8 hours since these were lab courses), but the biology department required a 4-hour prerequisite to these courses that was entitled Introduction to Human Science that was different from the 4-hour lab science general education requirement entitled Introduction to Life Science. Thus, a psychology major would graduate with 16 hours of biology courses. How could the mathematics and biology departments have this much effect on psychology requirements? Because the courses in question were in their turf and they were the best judges of what was needed.

You should have heard the cries of distress and the weeping and wailing when I strongly suggested that we cut back the average number of required hours by 20 hours. I was decimating majors. Graduates would never get into graduate schools. So where did the faculty find hours to cut? They agreed to limit the number of hours required for a major to 78 unless there was an outside accrediting agency requiring more. Although, in the first survey of the faculty they said that students needed more foreign languages, then they cut out entirely the general education 9 hour requirement in a foreign language, but added a new 3-hour course in cross-cultural communications. They cut the 12-hour requirement of sequences in both United States and World Civilization and added a new 4-hour required course in Western Civilization. How could the faculty make these changes? The Foreign Language Department and the History Departments were not members of large enough voting blocs to get the votes they needed to stay in as part of the general education.

These days were out and out turf wars. Intellect and intelligence were not very visible anywhere. It was a matter of who had the votes or what treaties you could make to get the votes. Who said there is no politics in education?

Teamwork is Critical: Learning with and from Others

One of the blessings of my current physical situation has been the opportunity to nventory anbooks on the d catalogue more than forty years of collected files and academy. While working full-time I never had the time to review all the files and books that I was collecting. These files and books were just piling up in my university offices and in my home offices and the storage areas of our homes. I had some idea of fwhat I possessed, but I didn’t know for sure. This led to duplication of files and books. As I have discovered these duplicates, I have given them to individuals who can ake good use of them.

However, the process of inventorying and cataloguing has also created a problem. In Chinese philosophy, this dichotomy, where opposite but complementary items form a complete whole, is known as yin and yang. The same situation is viewed by some people as a problem and by others as an opportunity. A modern western idiom attempting to express this is the question, “Do you see the glass as half-full, or half-empty?” I must admit that as I have inventoried and catalogued my collection of files and books, I have experienced both feelings. At times I am elated at the long hidden jewels of ideas and thoughts that I am finding in my files and books. As I consider these ideas I am easily distracted and start trying to track down more about the given topic. I find myself creating more files to add to my already abundant collection. When I try to return to where I was when I was distracted, I can’t find my place or I can’t get back into the flow of things. I am pleased that I have been reintroduced to many ideas that I had abandoned. However, I am frustrated that I can’t excavate around these ideas more fully. I am almost convinced that a life-time of thinking will take a second lifetime to explicate it.

One of the dangers when an academic picks up a book or an article is the temptation to scan it. Whenever I start to scan a book or an article, I find it almost impossible to put it down. It happened again and again as I went through my books and files. At one point, I came across a somewhat dated book with the intriguing title of Rural Development and Higher Education: the Linking of Community and Method, published by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. While I have been laid up, I have been reading and thinking about the development of American Higher Education. Recently, I was reading about the effect that the Morrill Acts and the establishment of Land Grant Colleges had on the overall development of rural America. My curiosity got the better of me, and I started scanning the Kellogg book. I was trapped. Soon I found myself reading the last chapter which was a summary of the nine Kellogg funded projects that were outlined in the book. The first section of this chapter was entitled, “Learning from others.” It began with a great story about “a city fellow who bought a thriving farm that had a new brood of baby chicks. A week later all the chicks were dead.” At this point the city fellow went to the neighboring farmer to find out what had happened and if there was anything he could do to prevent this from happening again when he bought some new chicks. The neighbor in all innocence asked the city fellow, “What did you feed them?” The city fellow was shocked and he stammered, “Feed them. I thought the old hen nursed them.”

The conclusion of this story is obvious. If you don’t know what you’re doing, it can be very dangerous to make faulty assumptions. In the setting of this book, the authors continued by suggesting that university faculty can’t hope to deal successfully with rural development if they presuppose full knowledge of the local needs, wants, and conditions of any given location and any given group of people. This led to the standard operating procedure within all Kellogg funded projects of forming a citizens’ advisory committee at the very beginning of the project. Everyone was constantly reminded that “Teamwork is critical.”

In higher education this is not only true when we are working on projects outside the institution, such as rural, urban, or industrial development. It is also true when we are working on a project inside the institution with our own students. How easy is it to assume we know what people need and what they already know? We can save a lot of time by just plowing in and developing assistance programs for them. Why should we ask students what they need? How absurd, they are only students! How many colleges and universities have set up student assistance programs to help students and find these programs don’t address the needs of their students?

Today almost everyone gives lip service to the adage that cooperation is the best policy. People know that generally you’ll get better results if you involve other people, seek their advice and help, early in a process. People are more willing to help and accept change if they have ownership in the process.

If teamwork was the most important lesson that the Kellogg Foundation learned from these projects, there was one more lesson that was a close second. This second lesson was that every project needs a project director who possesses the appearance of neutrality, “the statesmanship of a Disraeli, the leadership abilities of a wagon master, the selflessness of a missionary, and the energies of a long-distance runner.” These are great lessons for any organization to learn and master.

Students Are Paid To Not Attend College

The Chronicle of Higher Education posted an e-version of an article written by Ben WIeder, entitled Thiel Fellowship Pays 24 Talented Students $100,000 Not to Attend College. The Thiel in the title is Peter Thiel, cofounder of PayPal. The $100,000 Fellowships are meant to encourage 24 very talented students to spend two years developing their business ideas instead. The whole idea has created a stir in higher education circles.

The whole article may be found at http://chronicle.com/article/Thiel-Fellowship-Pays-24/127622/?sid=wc&utm_source=wc&utm_medium=en

One of the fellowship winners highlighted in the article is Jim Danielson, who was an electrical-engineering student at Purdue. Mr Danielson is quoted as saying he “learned more about his field on his own than in the classroom.”

This comment from Mr. Daniels reminded me of a portion of Mike Rose’s story, that he tells in his autobiographic book “Lives on the Boundary.” Mr. Rose’s related an incident from his graduate education in creative writing when he became overwhelmed with hour after hours, day after days of studying in the UCLA library, reading essay after essay about the poems they were reading in class. He finally gathered up all his courage and went to see the chairman of the creative writing program. Mr. Rose told the chair that we was learning more about the poems they were reading and studying in class by writing his own poetry. The chair shook his head,smiled and said in effect, “That’s not the way we study poetry here.” Some institutions will permit and encourage students to learn by doing, others do everything they can to discourage that type of learning activity.

I find this ironic since Aristotle said all free men should be educated in the three forms of knowledge, theorica, poeises and praxis. Theorica was the reflective contemplation of knowledge received through all of our senses (seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching); poeises was the production of objects of value (such as writing poems or painting a picture–poeises is the word from which we get our word poetry); praxis was learning by doing (praxis is the word from which we get our word practice – More than once people have said the only way to learn to teach is to teach, and that you really never learn medicine until you practice medicine.) It seems that poeises and praxis are both learning by doing. What’s the difference? I believe the primary difference is that the goal of poeises is to produce a product of value. It is to create an inanimate object of value; while the goal of praxis to enable the individual to affect changes in people whether oneself or others.

In many of our institutions, particularly liberal arts institutions, the primary, if not the only emphasis, seems to be on theorica. We also tend to restrict our sensory intake to seeing and hearing. In Ancient Greece, the full orbed theorica was held up as the pinnacle of knowledge. However, beyond a rudimentary introduction to it, further study in it was reserved only for superior students, the best of the best. Does this have any implications for our higher education system of today?

Request for help in tacking down quote about problem solving

Help, Please. I looking for the “famous” quote that I can’t remember and I can’t remember who said it. It is concerning the idea that using the same kind of thinking that got you into a problem will not get a solution to the problem. You must think “on a higher level.” Thanks in advance for your assistance.