From the comments I received after I published the recent post Are All Mathematicians Crazy?, it is obvious that I didn’t convince many readers that some mathematicians are almost normal. I readily admit that some mathematicians are off the chart on the eccentric side of the normality continuum. These famous curve busters make it difficult for the rest of us. There are mathematicians who indeed were strange birds and didn’t always fit the normal mode. They were different and stood out from their peers. Through the years, these unconventional mavericks have gotten most of the press coverage. Once you admit that you are a mathematician, you are automatically branded as different.

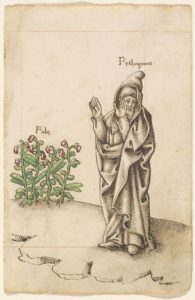

In a series of posts, I will discuss some of the more stranger mathematicians among us. The earliest outlier that I want to discuss is Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570 – c. 495 BC). He has been called by many the leading philosopher and ethicist of his day. Since there is no record of Pythagoras ever putting quill to papyrus, we have none of his works in his own words. All that we know of him and his teachings are what others have recorded. If half of the legends concerning Pythagoras are true, then in today’s vernacular, he could easily be labeled “a strange duck.”

Although he influenced many great philosophers, ethicists, and mathematicians, he is probably best known for the formula bearing his name, the Pythagorean Theorem, which states that the square of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. However, Pythagoras didn’t discover this formula since it was used in construction in Sumerian and Egyptian civilizations at least one millennium before he lived. It bears his name because Pythagoras is credited with the first generalized proof of this relationship, which is the proof I referenced in my previous post Are All Mathematicians Crazy?.

In terms of Pythagoras’ life, there are many contradictory stories. We believe he was born on Samos, a Greek Island in the Aegean Sea near modern day Turkey. His father most likely was a European merchant living and trading on Samos. Legend has it that Pythagoras, as a child and young man, traveled extensively throughout Asia, Asia Minor, Europe, and Africa. He reportedly sat under the tutelage of the best teachers and priests in Asia Minor, India, Egypt, and Greece.

We know that he was a gifted thinker and a great teacher. People traveled from all over the world to sit at his feet and learn from the master. He started a school known as the Semicircle since that was the shape of the Pythagorean classroom. This classroom model is still very common in college settings today. Pythagoras would take center stage with a clear view of all students, while the students could see all other students and direct answers and questions directly to them as well as the teacher. However, students have always been students. Notice the lack of attention on the face of the one student in the foreground, staring off into space. Even the great teacher Pythagoras couldn’t keep her attention.

In the illustration of the Pythagorean School, most of the students depicted are women. Pythagoras was the first Greek philosopher or teacher who advocated education for women. He was also the first prominent Greek to promote monogamy within marriage. His influence on women’s rights and the education of women was felt for centuries.

From his time in an Egyptian temple, he may have picked up his ideas on metempsychosis, the belief in reincarnation. It is reported that Pythagoras could recall all of his former lives. He entertained his students and followers for hours on end with stories of his former lives. Since he believed that he was there in one of his former lives, he supposedly enthralled his listeners with vivid accounts of the great battle and fall of Troy. In at least one incarnation, Pythagoras was supposedly a beautiful courtesan, a prostitute who lived an unhappy and unfulfilled life in the lap of luxury, courtesy of her wealthy customers. Some writers attribute his high regard for women to the time he spent as this oppressed woman with few rights.

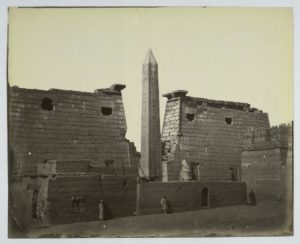

While in Egypt, it has been reported that he was admitted into the priesthood at the Temple of Karnak near the cities of Thebes (Greek name: Diospolis – city of the gods) and Luxor. If true, he would have been the only non-Egyptian to have ever been granted this great honor. Supposedly he learned much of his geometry from the Egyptian priests. They also instilled in him their lifestyle and moral codes, which included abstinence from sexual pleasure, and avoidance of clothes made from animal skins. The Theban priests were vegetarians with one quirk. They refused to eat or even touch beans. This unusual behavior was apparently well-engrained into Pythagoras.

Pythagoras studied at Luxor for ten years until Cyrus and the Persian army defeated the Egyptians in 526 BC. In the battle for Thebes, the Persians killed Egyptian Pharoah Psamtik III, son of Amasis II. The Persians were so enamored by the size and beauty of the Luxor Temple that they ordered the defeated Egyptians to rebuild Thebes and repair all damages to the Luxor Temple. The Persians were also impressed with the intelligence of Pythagoras, a Greek they found among the priests at Luxor. They took him captive back to Babylon, where he studied under the wisest sages of Persia for another ten years.

Many historians believe that after leaving Egypt, Pythagoras had a life-long battle with an irrational fear of beans. If the legends are correct, his leguminophobia may have cost him his life. Years later when his school at Croton in Italy was attacked and destroyed, Pythagoras supposedly escaped. While running away from the attackers, he stumbled upon a field of beans. He froze in his tracks and would not go any further. According to one legend, the rioters found him terror-stricken, cowering at the edge of the field he had refused to enter. They proceeded to beat and club the old man to death.

According to a second legend, the rioters knew Pythagoras was deathly afraid of beans. Thus, they never searched for him in the vicinity of the bean field because they knew that Pythagoras would have never approached it. After hiding in the weeds on the edge of the bean field for a long time, Pythagoras returned to his school. Seeing that it was destroyed and many of his students killed, he left Croton for Metapontum to escape persecution for his anti-democracy teachings. In Metapontum, he supposedly hid in the Temple of the Muses. He reframed from eating because the priests of the Temple didn’t provide the vegetarian diet he requested. They offered him meat and beans. After 40 days of a self-imposed hunger strike, he died of starvation in the temple.

There are many other stories and legends of the exploits of Pythagoras. If only a small fraction of them were true, Pythagoras was indeed different and could be considered a strange duck. The next unusual mathematician that I will consider is Archimedes. In the meantime, I will return to my series on the changing scene in American higher education.