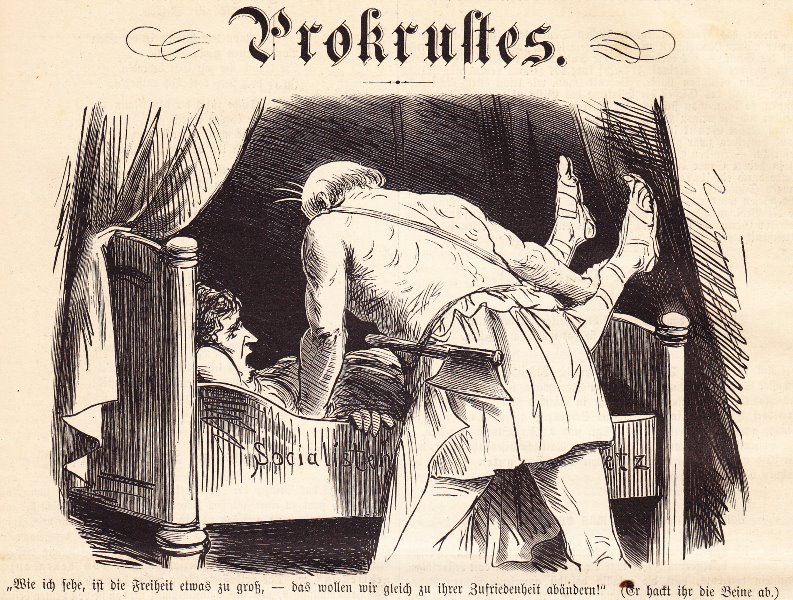

I don’t know how to say it any clearer. I have come to the shocking conclusion that the enterprise of American education is doing society a huge disservice by propagating and perpetuating a big lie. Please do not misinterpret what I am attempting to say in this essay. I am firmly convinced that education is immensely valuable. Paraphrasing a credit card commercial campaign, it is “priceless.” For more than 65 years, my life has revolved around faith, education, and family. I am fully committed to the concept of an appropriate education for everyone. However, I am also very certain that education, as it is currently conceived and generally defined, doesn’t and can’t serve everyone equally well. To paraphrase a television commercial for a particular internet service, “Education that doesn’t serve everyone, doesn’t serve anyone.” The simplest statement of Education’s Big Lie is Procrustes’s aphorism “one size fits all.”

By “one size fits all” I am surprisingly not referring to either standardized testing or the Common Core. Both of these educational fads have their good and bad points. I will explicate my views on each of them in later posts. For this post, I return to a fuller statement of my understanding of the Big Lie plaguing the American educational enterprise. The reality to which I am referring is that the American educational enterprise has pigeon-holed the mental characteristics of creativity, imagination, intelligence, curiosity, ingenuity, reasoning, and problem-solving primarily if not exclusively to the verbal region of the human brain. The Big Lie equates these characteristics with one’s facility with words. Many if not most of the instruments used to measure these mental characteristics are primarily verbally based. To improve their abilities in the areas delineated above, students are instructed to read, write, and speak more.

This solution may work for many and possibly the majority of students. However, the problem with this remedy is that for a significant number of students words are more like enemies than friends. Words are at the crux of my argument against education. Ideas are considered the coin of the realm in education. For centuries in education, we have been indoctrinated to believe that ideas are formulated almost exclusively through words. After ideas are formed, we must then use words to express those ideas, either in written or oral form. We are taught that to think properly we must use a process that is based in and undergirded by the use of words. This process is commonly known as verbal thinking. I grew up with that mindset. In this mindset, words are the cornerstone upon which we build our ideas.

This was the way I was taught. It is the way most of our American society has been taught for hundreds of years. I am going out on a limb now and say that this is not the only way we think or must think. It took two traumatic brain incidents (TBI’s) in 2009 to convince me that there are other ways to think. The first TBI was the implosion of a benign meningioma due to the explosion of the artery which was feeding it. This TBI left me with a mild case of aphasia. As a verbal thinker, I found it difficult to think when I couldn’t find my beloved words.

The second TBI was a series of four tonic-clonic seizures within 30 minutes that left me in a coma for three days. When I woke up, I knew immediately something was different. I found myself no longer going directly to words to make sense of what was going on around me. I saw pictures. At first, I wasn’t certain what had happened. As I reflected on what was happening, I remember several articles that I had read that were written by stroke survivors. I was having the same experiences that they had encountered. I had become a visual thinker.

After 60 years of being a poster child for verbal thinking, words were now my second thought language, Although I was thinking in terms of pictures, I found that it was necessary for me to use words to communicate my ideas. This was extremely frustrating at times. I attempted to describe my feelings in a 2010 blog posting entitled Words Are More Like Cats Than Dogs.

Where am I going with this argument? For centuries in educational circles, words have been king.

A recent Google+ posting The Importance of Imagination by Elaine Roberts, a former colleague, induced me to write this series of posts. In her posting, Roberts described a situation that led her to an epiphany and two points of clarity. The situation grew out of an attempt by a teacher to test or evaluate the creativity of a class of sixth graders. This teachers’ attempt was not a standardized test. It was a writing assignment. Most educators would label this assignment as an authentic assessment instrument. The teacher gave the children the following set of instructions:

What do I imagine some of the students heard? “Blah, Blah, Blah!”

Even though they had previously been given a template to use in writing stories, what were the first thoughts of some students about constructing a story? I think they probably drew a blank.

Even though they had previously been given a template to use in writing stories, what were the first thoughts of some students about constructing a story? I think they probably drew a blank.

Taking literary license with this scenario, what did I imagine this student wanted to turn into the teacher? Simply, a blank piece of paper.

What do I think the teacher’s response to a blank piece of paper woul be? Most likely, he would have said to himself, “What is wrong with this student? The wiring in his head must be all tangled up.” Now the shoe is on the other foot. The teacher doesn’t know what the student is trying to say.

With respect to the spread of the Big Lie, I readily admit that my hands are not entirely clean. Prior to 2009, as I noted above, I could have been considered a poster child for verbal thinking and verbal learning. In all of my recollections of my earliest childhood, I was constantly immersed in books and words. At the age of five, I won a Sunday School contest for being the first primary student (Grades K through 6) during the new church year to recite 100 selected verses by memory.

As an academic professional, I made my living off words. Even as a mathematician, my training, and education were dominated by words. As an instructor, I constantly fed my students words.

As an administrator, I used words to defend positions and try to persuade colleagues to follow my lead.

With what I have written so far, I should probably call it quits for this first post in this series. If I haven’t done enough to damage my image and credibility within the higher education community, I invite you to stay tuned for additional posts. Although it has been difficult at times, I have learned that we can think without words. In fact, I have subtitled Part II of the series Education’s Big Lie, “We Can Think without Words.” Even though we give lip service to the idea that “A picture is worth a thousand words”, in much of today’s world, particularly those parts of it touching the education enterprise, the most difficult aspect of working with thoughts and ideas is trying to communicate them without words.