Some historians of American Higher Education call the era between the American Civil War and WWII the Gilded Age of American Higher Education. When I look at it, I see a period of unparalleled expansion, confusing disruptions, and bewildering rearrangements. It is also a period rife with widespread uncertainties and inescapable paradoxes. It is a period of unprecedented diversification.

During the Civil War, much of American higher education shut down. Many colleges were forced to cease operations due to a lack of students. In both the North and the South, many young men of military age either enlisted or were drafted. Since this group formed the overwhelming majority of college students, the potential student population was almost completely depleted.

The stories of what four institutions. Hampden-Sydney (with its sister school Union Theological Seminary), the United States Military Academy at West Point, and the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, went through during the Civil War Period are so interesting I will address them in a separate, future post.

Since much of the actual fighting in the Civil War occurred in the territory of the Confederacy, a large number of colleges in the South found themselves in battle zones. A few colleges in the North, like Pennsylvania College (since 1921, known as Gettysburg College) and its sister institution Lutheran Theological Seminary, were also put in dangerous situations. This placed students and faculty at severe risk. Travel was treacherous at best. Students from the Confederate States who were studying in the Union States, and vice versa, were prohibited from crossing territorial or battlelines and were forced to withdraw from their colleges.

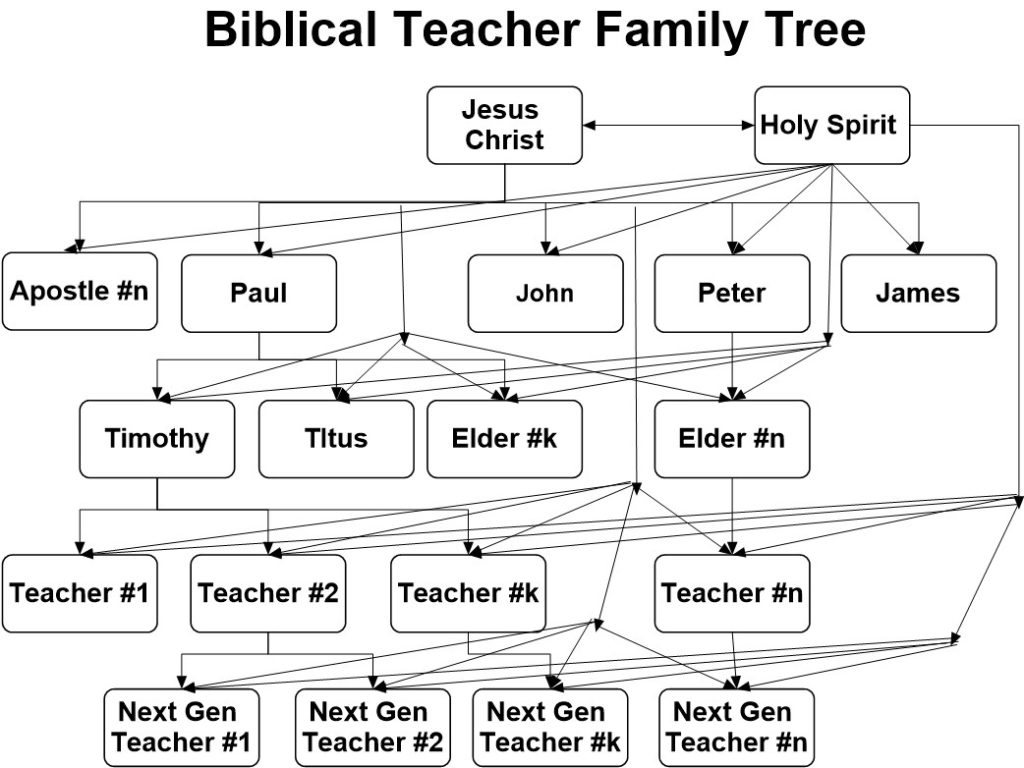

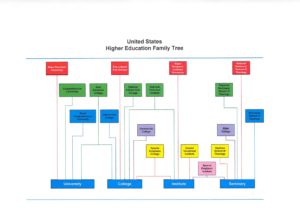

During the eight decades between the Civil War and WWII, the current structure of American higher education began to take shape. Prior to the Revolutionary War, all colonial colleges were begun with a religious emphasis by individual clergy or denominations. These schools were founded to provide an educated clergy for the church. Studying the early days of these institutions, we also see that they were not in the business of changing the social stratification of the colonies.

Most of the colleges established between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars were built to maintain the status quo. They only enrolled white, males. They were expensive, residential institutions, which meant that the “lower class” families could not afford the luxury of doing without the income supplied by the family sons. Entrance requirements of many were rigorous and only within the reach of the wealthy few who had the advantage of a demanding secondary education.

The few female colleges were also expensive, residential colleges that trained girls to be “ladies”. These schools were beyond the reach of most families and didn’t fit the long-term goals of most girls in America.

Prior to the Civil War, there were very few coed colleges. There were also very few female applicants who could meet the admissions requirements. There were only a handful of colleges open to African-Americans. Colleges prior to the Civil War were the great sustainers of an elite hierarchy with white males at the top of the ladder. Many obstacles were placed in the paths of others trying to ascend the ladder of social mobility.

Immediately after the Civil War, the dams of restrictive access were leaking a little, before they finally burst. In those early post-war days, a number of changes occurred. It became more acceptable for women to attend college. More women colleges were opened, and more colleges permitted men and women to sit in the same classrooms.

A second new stream of students consisted of the returning soldiers. Their war experience awakened new dreams. They saw that the only difference between them and many of their “educated” officers was formal education. The rank and file soldiers found that they were just as smart as their officers. They began to question why had they been deprived of an opportunity to advance themselves. They demanded the right to go to college, and some colleges opened their doors to these new students. However, more than college for themselves, they demanded college for their children so that they could better themselves and not be limited to the status of a lackey or foot soldier in the future.

A third stream formed with the opening of colleges for African-Americans. At first, this was a small stream because these students had many deficits to fill in from their lack of education prior to the Civil War.

In 1860, there were less than 10 institutions of higher education which were open to African-American students. By 1900, there more than 100 institutions that were dedicated primarily to the education of African-American individuals. These schools became known as Historical Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU).

A fourth stream formed with the demand for specialized training and education. Career colleges, business schools, technical and engineering institutions, art schools, research universities, Bible colleges and seminaries, agricultural schools, medical specialty colleges, nursing schools, and law schools began popping up in every corner of the growing country.

Another new strand of higher education emerged in the first decade of the 20th century, the community or junior college. These colleges were designed to offer the first two years of a general college education and permit their graduates to then transfer to the four-year colleges and universities. Joliet Junior College in Illinois was the first public junior college. It opened in 1901.

Previously, colleges were primarily residential and located in rural or semi-rural settings. But now urban students demanded and got schools in the middle of cities. These students didn’t want the residential experience, so a new type of commuter college was invented.

Schools like Central City Commercial College (4C), which opened in Waco, Texas, in 1924, met the need of urban residents for training in employable skills or retraining in new skills. In 1935, 4C expanded its evening programs in order to accommodate shift workers who wanted to learn new skills.

Prior to the Civil War, most colleges were founded under the flag of religion. By the time the Civil War began, many of these institutions had drifted from their religious moorings. Some had become secular institutions, while others had their ownership assumed by governmental agencies and had become public institutions.

After the Civil War, three separate strands of institutional control were formally recognized. The first strand was public institutions, which were primarily funded by governmental agencies such as states, counties, or cities. These institutions were kick-started by the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890, also known as the Land-Grant Acts. These pieces of legislation provided grants of land to states to finance the establishment of colleges specializing in Agriculture, Home Economics, the Mechanical Arts, and other useful professions. Public institutions began to dominate higher education with their seemingly untouchable advantage of an apparently unending supply of tax revenue.

The second strand consisted of private, non-profit institutions. These were chartered by states, but controlled by independent boards. Some of these were sectarian in nature. They were founded by, controlled by denominations or churches, and funded through the religious founders. Others were non-sectarian, without any particular religious bent.

The third strand was the proprietary schools. These consisted of schools typically founded by an entrepreneur who viewed the institution as a profit-making venture. They were chartered by states, but controlled by the founder or a board of trustees, similar to a corporation. These three strands still dominate the higher education scene of the 21st century.

Diversity in these colleges was not just limited to the type of control, students, programs offered, or geographic location. Students began choosing colleges for more reasons than particular academic programs. They began including in their selection processes non-academic programs like athletics, debate teams, musical opportunities, both vocal and instrumental, and social organizations.

Rutgers University defeated Princeton in the first intercollegiate football game on November 6, 1869. The University of Michigan’s football stadium, Michigan Stadium (known as the Big House), was built in 1927 with a capacity of 72,000. It soon outgrew it and added 10,000 more seats within five years. The stadium was formally dedicated on October 22, 1927, when Michigan beat Ohio State before a standing-room-only crowd that exceeded 84,400 people. College sports had become a big-time business. Colleges began recruiting athletes to attend their school in order to play for them.

Intracollegiate debating on college campuses seems to have originated in literary societies as early as 1830. The first recorded intercollegiate debate may have been between Wake Forest University and Trinity College (later known as Duke University) in 1897. Soon debate teams were touring the country, holding matches and tournaments. The movie “The Great Debaters” memorializes a 1935 debate team of African-American students from Wiley College (Marshall, TX) which supposedly traveled to Harvard University, and defeated the reigning national championship debating team. In reality, the debaters from Wiley did not debate Harvard. They debated and defeated the reigning national debate team from the University of Southern California. However, the Wiley team could not declare themselves victors because African-Americans were not permitted to join the Debate Society until after WWII.

James Farmer, Jr., was recruited as a 14-year old freshman by Melvin Tolson, the founder, and coach of the Wiley College Debate Team to become a valuable member of this formidable debating powerhouse. He went on to a have distinguished career in civil rights work in the United States in the middle of the 20th century.

James Farmer Jr. was considered one of the “Big 4” in the civil rights world. The first of the other three was Martin Luther King Jr. (1948 graduate of Morehouse College an HBCU institution in Atlanta, GA), and founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The second was Whitney M. Young Jr. (1941 graduate of Kentucky State University and HBCU institution in Frankfort KY) who served as the Executive Director of the National Urban League, transforming it from a passive organization into an aggressive force working to give socioeconomic access to all individuals who had been historically disenfranchised. The third member of the group was Roy Wilkins (1923 graduate of the University of Minnesota which had a long history of accepting African-American scholars and students), who was Executive Director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People from 1955 to 1977. Roy Wilkins was one of the primary organizers of the 1963 March on Washington. In 1967, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian decoration.

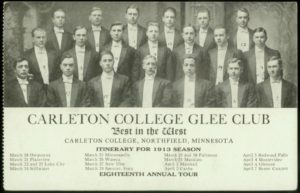

Glee Clubs were small choral groups dedicated to singing glees, short secular choral songs, which were written or arranged for several vocal parts. These clubs originated in London in the late 18th century and made their way to the American college campuses in the mid-19th century. The first documented American collegiate glee club was founded at Harvard University in 1858.

By 1910, there were more than 100 colleges hosting Glee Clubs. Many of these co-curricular clubs were replaced on campuses by larger choral groups and formal choirs which performed under the auspices of the music department or school. Many of the colleges would sponsor the Glee Club tours for fundraising and student recruiting purposes.

Historically marching bands were associated with military ventures. They consisted primarily of wind, brass, and percussion instruments. By the middle of the 19th century, they found their way onto college campuses. The first official collegiate marching band was the University of Notre Dame Band of the Fighting Irish, founded in 1845. It first performed at a football game in 1887. By the end of the 19th century, hundreds of American colleges and universities hosted marching bands and orchestras. In 1907, the Purdue All-American Marching Band unveiled the first pictorial formation on a football field with their rendition of the Purdue “Block P.” Not to be outdone, later that year, the University of Illinois Marching Illini band performed the first full halftime show at the football game between the University of Illinois and the University of Chicago.

Colleges and universities began recruiting students to perform in their vocal and instrumental musical groups. Other performing arts, like drama and dance, soon followed. Colleges and universities became cultural centers, not only for students but for the communities in which they were located.

Fraternities, sororities, and other social clubs dated their beginning on American campuses from December 5, 1776, with the founding of the Phi Beta Kappa Society at the College of William and Mary. Between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, fraternities and sororities developed slowly. They were primarily centered in the Northeast quadrant of the United States.

After the Civil War, with the great expansion of colleges and universities, fraternities and sororities also flourished. The American higher education system began encountering racial, religious, and gender diversity and new colleges were founded or reformed throughout the south and west. Growth in the fraternity system overall during this period would lead some to label the last third of the 19th century as “The Golden Age of Fraternities.”

However, the diversity of institutions which engendered a diversity of students also had a darker, hidden side. Students looked to the fraternities and sororities not as vehicles to encourage diversity, but as avenues of escape and as a way to avoid associating with large numbers of particular types of students. They became vehicles of discrimination.

Thus the period between the Civil War and WWII was an era of growth in terms of the number of students and the diversity of types of institutions, types of campus activities, and diversity of students within the system as a whole. Paradoxically, it was also an era of rampant discrimination and exclusion. WWII produced another pause in the development of the American higher education system. We pick up that story in the next post.