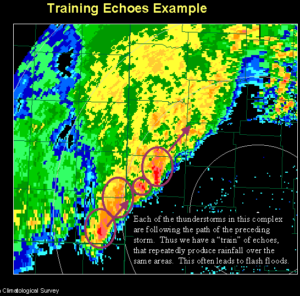

In the last quarter of the 20th century, American higher education was battered unrelentingly by storm after storm. In weather terminology, meteorologists call this phenomenon “training”. This name is derived from how a train and its cars travel along a single path, the railroad track, without the track moving. With repeated precipitation hitting the same geographic area, this weather pattern often produces heavy damage caused by flooding. American higher education has been heavily damaged by a constant barrage of storms.

There is little debate concerning the results of the numerous storm trains which assailed American higher education. It left AHE in shambles. To many observers, health-wise AHE was in critical condition. The blue light was lit and the warning alarm sounded. The critical response team was called into action. The condition of American higher education had definitely reached the crisis stage. Danger lurked around every curve on every track. Educators and politicians held their breath because another potential train wreck could happen at any moment.

When one car derails in a train wreck, it usually takes many, if not all of the cars behind it off the rails. Since the cars are all connected, sometimes the sudden stop of a car in the middle of the train will even cause the cars in front of it to crash also. Trailing cars will pile up on the initial crashed car, scattering debris in every direction and causing much collateral damage.

With “training storms” the accumulation of the falling precipitation can eventually cause flooding. This flooding will be greatly exacerbated by the following storms, multiplying the damage. With multiple storms dumping rain on one spot, the flooding deepens at that location. It will eventually spread, affecting adjacent locations. The crisis has become a full-blown disaster.

As flood waters began to engulf American higher education, many commentators and most politicians started calling for disaster aid. They wanted some entity to act as the educational equivalent of FEMA, They were clamoring for someone to step in and rescue what they saw as a failing system. This vocal group will have to wait a long time because there is no educational equivalent of FEMA. In addition, many within higher education believe and strongly avow that the system is not failing. It is the public, along with the federal and state governments that are failing higher education.

What ended the Golden Age of American Higher Education and seriously damaged a system that was the envy of the whole world? In many accident investigations, it is difficult to identify a single event or factor that caused the mishap. Much of the time, there is a series of events or determinants that contribute to the incident. What was the series of events that caused the train wreck which derailed American higher education?

My self-identified list of the causes of rail accidents included the following items:

- Human error

- Environmental conditions

- Mechanical failure

- Infrastructure deterioration and collapse

- Speed

- Design flaws

- Unintended obstructions

- Sabotage

- Combination of problems

As I have analyzed the difficulties that American higher education has faced in the last quarter of the 20th century, I believe that most, if not all of them, can be attributed to one or more items in the above list. I will use the remainder of this post to list specific events that contributed to some of the more serious disruptions during this tumultuous period in the history of American higher education. Speculation concerning the assignment of blame for those disruptions, and possibly others, will have to wait for future posts.

The first two events that led to the End of the Golden Age of American Higher Education were the end of the Vietnam and Cold Wars. These are the primary counterexamples of the axiom which states that the end of an American war produced a boom in education in the United States. What were the differences between the Vietnam war and the Cold War and other American wars?

The Vietnam War might arguably be the most unpopular war in the history of the United States. People didn’t know or didn’t believe the reasons given by politicians and military leadership as to why young American soldiers were being sent to Southeast Asia to fight and die at the hands of an unknown enemy. With a military draft in effect between 1964 and 1973, many young men used academic deferments as a means to avoid military service. The term “draft dodger” became a common insult that was hurled at these individuals.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, young men avoiding military service swelled the enrollment ranks at many colleges and universities. They became a vocal part of the social activism that was growing up on American campuses during these turbulent years. College campuses became the hotbed of dissent not only for an antiwar movement but also for all forms of militant protests for social justice, civil rights, and alternative lifestyles.

One of the most violent protests occurred on the University of Wisconsin – Madison campus in the early morning hours of August 24, 1970. Four students detonated a bomb in a stolen truck that was parked next to Sterling Hall which housed portions of the UW-Madison Mathematics and Physics Departments, including the Army Mathematics Research Center, which was the primary target of the bomb. There were only four people in the building at the time of the explosion. A physics post-doc doing an experiment on the ground floor was killed and three others on higher floors were injured.

During Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign, he promised to eliminate the draft. However, after assuming office, this proposal was met with great opposition to the idea of an all-volunteer army from both Congress and the Department of Defense. Instead of acting immediately on his promise, Nixon appointed a commission, chaired by Thomas Gates, former Eisenhower Secretary of Defense.

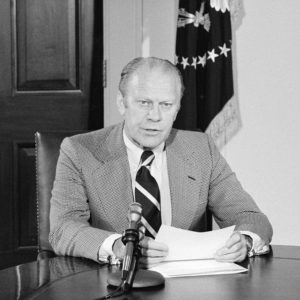

under the digital ID ppmsca.08536. This work is from the U.S. News & World Report collection at the Library of Congress. It is part of a collection donated to the Library of Congress. Per the deed of gift, U.S. News & World Report dedicated to the public all rights it held for the photographs in this collection upon its donation to the Library. Image courtesy of U.S. News and World Report, the Library of Congress, and Wikimedia Commons.

The Gates Commission studied the idea for a year, issuing a report in February 1970, suggesting that an adequate military force could be maintained without conscription. When the existing draft law expired in June 1971, the Department of Defense successfully argued that it needed more time to institute all of the Gates Commission’s recommendations. Congress agreed and extended the draft until June 1973. Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate scandal and his subsequent resignation on August 9, 1974, prevented him from seeing the Gates Commission recommendation put into place.

In anticipation of the end of active ground participation in Vietnam, the last draft was held in December 1972, of men born in 1952. The end of the draft contributed to a noticeable decrease in men applying to college in the mid-1970s. The last impediment for the anti-war objectors having to choose between fleeing to Canada for sanctuary or attending college for an education, in order to stay out the army, was removed on September 16, 1974. On that date, President Gerald Ford announced from the White House a complete and total amnesty for draft evaders.

In conventional wars, soldiers participated in armed conflicts and thus were unable to engage in collegiate studies. One million soldiers landed on the beaches of Normandy between June 6 and July 30, 1944. Each day, these soldiers were fully engaged in a life and death struggle, and could not have devoted any time to academic pursuits. When the armed conflicts ended, soldiers were freed to advance themselves through college studies. After WWII and subsequent wars, the various GI bills allowed veterans to enter college or career preparation programs. After WWII, almost half of the 16 million eligible veterans enrolled in some type of educational program. After the Koren War, 43% of eligible veterans used educational benefits. After the Vietnam War, an enormous 73% of eligible veterans used educational benefits. However, there were only 2.7 million eligible veterans after the Vietnam War. Thus the 73% benefit usage percentage produced just under 2 million students, compared to the almost 7.8 million after WWII and 2.1 million after the Korean War. This smaller number of actual students didn’t produce the enrollment bumps that occurred after the earlier wars.

The Cold War was a completely different kind of war. It was a battle for scientific superiority. The battlefields were the college classrooms and laboratories. The Cold War itself was a huge incentive for students to enroll in colleges and further their education. By doing so they were not only furthering the cause of their country, they were increasing their opportunities for social and financial upward mobility. The actual effect of the Cold War enrollment bump is hard to determine because it came at the same time as the last of the Baby Boomers and the first of the Gen Xers came of college age. The Gen Xers had the greatest college enrollment in American history. College enrollment of this generation of students compared to previous generations exploded.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Empire were emblematic of the end of the perceived Soviet threat to the American way of life. Without that driving force, the massive universities and college systems that grew up in the 50s and 60s found themselves as superfluous. The generous public support that had been so ubiquitous during the Cold War suddenly disappeared. In 1980, with the election of Ronald Reagan as President, the amount of public funding in cost-of-living adjusted dollars allocated to education started to decline for the first time in American history.

Without the immediate threat of an external enemy, the American public turned its attention to internal needs and desires. Suddenly, there were other public services competing with education for the limited available public resources. These other services included transportation and infrastructural needs, emergency services, judicial and penal services, public utilities, social and welfare services, services for an aging population, and affordable medical care. In the 1980s, with the U.S. population becoming much more concentrated in urban and suburban centers, the other services began to win more of those funds.

To appease their ravenous appetite for more of everything, without government funding, the colleges and universities turned to the next most available source of funding — their students. The total cost of college, including tuition, fees, room, and board, rose almost 400% from 1975 to 2000, while the General Cost of Living Index only rose a little over 200%. During this period college costs were rising almost twice as fast as the general cost of living.

As a bone tossed to the vulnerable students and their families, colleges increased access to financial aid. However, the overwhelming majority of these increases in financial aids were in the form of loans instead of grants and scholarships. This meant that those increased costs would have to be paid by the students sometime in the future.

With the increased availability of student loans, another problem surfaced. After students left college, whether or not they graduated, those loans came due for repayment. Another storm was brewing and another train car in danger of derailing. By the mid-1980s, students and parents had incurred nearly $10 billion in federal student loans. In 1986, more than one-quarter of all student borrowers had outstanding student loans of more than $10,000.

In 1990, the typical college student graduated with a median debt of just over $12,000. That graduate going out into the workplace could look forward to a median starting income of slightly over $43,000. This is a debt to salary ration of 28.6%. By the year 2000, the median college graduate left school with a median debt that had almost doubled to $22,500. However, the median starting salaries of college graduates had decreased by 1% to just over $40,000. This means that the debt to salary ratio had almost doubled to just over 56%. If these numbers were not shocking enough, tougher times were just around the bend.

In my next post, I will look at the continuing turmoil and disruption of American higher education that carried over into the first two decades of the 21st century. We will consider how the student debt bubble, exploding tuition costs, several recessions, proprietary institutions, and technology challenged the status quo and balance of the higher education arena.