This is the fourth part in a series on the economic conditions in higher education. The preceding post, The Business Model of All of Higher Education is Broken: Part III — Tuition and Fees, dealt with the history of the revenue stream generated by tuition and fees over the past 40 years. American higher education is divided into two main segments: public education and private education. Much of the American population has a giant misconception about how American higher education is funded. Most students and their families know full well the real financial burden that an education puts on their own budgets. However, it seems that many Americans believe that between government subsidies and the revenues generated by tuition and fees, both public and private colleges cover all of the educationally related expenditures of these colleges. Most surveys suggest that the American population does not believe that American higher education is experiencing a real financial squeeze. On the other hand, surveys such as Inside Higher Ed’s Annual Survey of Chief Business Officers, tell a very different story. More college officials are starting to worry about the future of American higher education. While this debate rages, some current politicians are espousing the idea that the public institutions should be tuition free. Many independent analyses of this idea suggest that there are untold, hidden dangers in this bold plan. It looks like I just suggested the addition of at least two more posts to this series on The Business Model of All of Higher Education.

However, as promised this post will concentrate on the question of how much of college budgets are actually covered by students’ tuition and fees. The most recent compendium of cost data is from the January 2016 Delta Cost Project, at the American Institutes for Research (AIR), Trends in College Spending: 2003 – 2013. This report is the most recent in a series of reports sponsored by the American Institutes for Research (AIR). These reports focused on two questions: 1) Revenues: Where Does the Money Come From? and 2) Expenditures: Where Does It Go? What Does It Buy? In addition to the Delta Cost Project, expenditure data can be extracted from the Integrated Postsecondary Educational Data System (IPEDS) data base. Unfortunately, the Delta and IPEDS data do not segment their data in the same manner. In addition, the Delta study has not consistently used the same segmentation.

The Delta Study prior to 2013 used only six segments of institutions. There were three for public institutions: Research Universities, Master’s Universities, and Community Colleges. The three private categories were: Research Universities, Master’s Universities, and Bachelor’s Colleges. In 2013, the Delta Study added a seventh segment: Public Bachelor’s Colleges. In attempting to extract the data from the IPEDS data base, one must be careful because some college and university systems submitted data for individual institutions, while others submitted system-wide data. In using the IPEDS data for this post, I tried to break down data into seven segments. I can’t guarantee the absolute accuracy of all of my calculations. However, since the data seemed to fall in line with the Delta data, I am comfortable in using my data for general inferences.

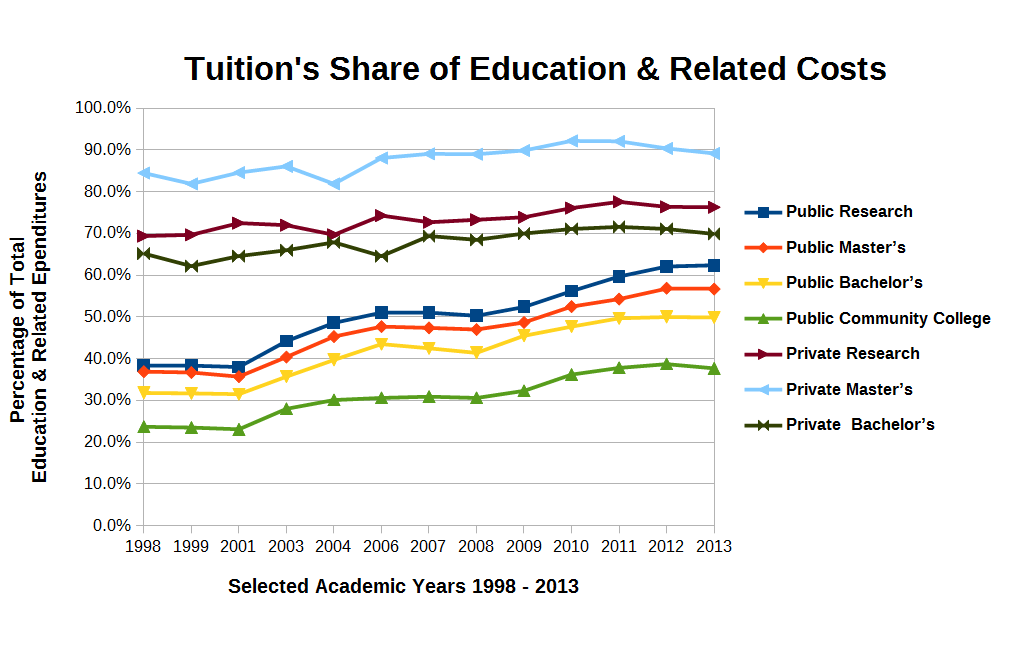

There are at least four mysteries or questions that we can derive from the data in the chart above. The first is that the private institutions use more of tuition dollars to pay for Education and Related Costs (E&R Costs). This is not totally unexpected since public institutions by definition get more support from governmental sources. There is another question lurking in the weeds. The graph of E&R Costs for private institutions are much closer to flat lines than the more sharply increasing lines for public institutions. What are the causes of these sharp increases? Is this a subject for another post?

In terms of funding for Public Institutions of Higher Education (IHEs), federal and state politicians have been passing the football back and forth like a hot potato for the past quarter of a century. After many years of stability or growth, the percentage of total spending at state universities provided by state tax revenue has been sinking since 1990. In attempting to explain drastic increases in tuition and fees for Michigan residents, Jim Duderstadt, President of the University of Michigan from 1988 to 1996, told students, state legislators and the general public, “We used to be state-supported, then state-assisted, and now we are state-located.” In the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the State System of Higher Education is comprised of 14 “state owned” universities. The state contributes $3,900 annually per student while in-state students pay $10,052 annually in tuition and fees. For the state-supported, flagship institution Penn State University, in-state students pay $17,514 in tuition and fess while the state contributes $3,000. Michigan and Pennsylvania are not the only two states that have “privatizing public higher education.” Thomas G. Mortenson began a Winter 2012 post, State Funding: A Race to the Bottom, on the American Council on Education (ACE) website on the Leadership and Advocacy page with the following statements:

In fact, it is headed for zero.

Based on the trends since 1980, average state fiscal support for higher education will reach zero by 2059, although it could happen much sooner in some states and later in others.

I have one question for all the zealous politicians calling for tuition-free, or even debt-free public education: “Flying in the face of these current trends, where are you going to get the money to make up these differences?” These conundrums sound like the material for additional posts.

The second question raised by the chart, Tuition’s Share of Education & Related Costs, relates to the percentage of student tuition dollars that Private Master’s institutions devote to E&R Costs. These data help bring to light one of the most poorly kept secrets in higher education. Master’s programs can be cash cows for institutions. Traditionally, many master’s degree programs, such as MBA’s, MED’s, and MA’s in humanities, have not given out large amounts of financial aid to students. Master’s degree students in these areas come to the institutions without any expectation of financial aid from the institution, nor from current employers, if they have current employers. Thus, they tend to pay full tuition out of their own pockets, using loans to make up any differences they can’t fund out of their own savings and earnings. This frees up more money from the subsidy sources for institutions to use in other ways. Do these points provide us topics for additional posts?

The third question relates to three obvious declines in the percentage of student tuition dollars used to fund E&R Costs in the above data. The first two occurred in 2003 in the Private Research and Private Master’s universities. There are also drops in the Private Bachelor’s colleges and Public Master’s universities. These occurred in 2004 and 2006 respectively. This question has two parts. The first part is “Why did institutions decrease their dependence on student tuition dollars?” The second part is “Why did these declines occur at different times?”

The fourth mystery relates to the relative slope of the graphs of the public institutions. The Public Community Colleges have the slowest growth rate of all public institutions. Why have they been able to keep from dipping into the student tuition dollars to fund more of the E&R Costs? Do they know something or are they doing something different from the public four-year institutions? Is this a topic for another post?

I believe that I have come to a good transition point in this discussion of Tuition and Fees providing additional funds for American colleges. If we can’t raise what each student pays, the next logical choice would be to get more students paying the base tuition and fees. The next post will deal with the problems of increasing the number of paying students going to college.