American Higher Education (AHE) has lost its lodestar. This post has been a lot harder to write than I thought it would be. At first, I was extremely excited to write this post. However, as I began to compose it, I immediately hit a number of roadblocks.

The first roadblock related to the way I process thoughts and ideas. As many of you know, almost a decade ago two traumatic brain incidents drastically changed my life. After a burst aneurysm caused the implosion of a benign meningioma attached to my right temporal lobe, I started having trouble finding words. I found myself fighting a case of oral aphasia.

Nine months later, I experienced four tonic-clonic seizures within a thirty-minute timespan. When I awoke from a four-day coma, I found myself no longer thinking in terms of words. I was now processing thoughts and ideas in terms of pictures. Words became my second language. Visual images were now my first language. This meant that in order to communicate with people, I had to translate back and forth between pictures and words.

My mind was overflowing with pictures that spoke to this issue of American higher education. However, translating those visuals into words was much more difficult and slower than usual. If I was able to compose other posts, why had this particular post become so problematic?

During my struggles with this post, I had a eureka moment. In the deep recesses of my mind, I found a perfect word, LODESTAR, that covered four aspects of the topic I wanted to address.

First of all, a lodestar is a fixed point of reference, which can be used to describe the position or motion of one object relative to another object.

There have been dramatic changes in both American higher education and society during the past century. AHE needs a lodestar to position itself in relation to American society.

Secondly, as a fixed point, a lodestar can be used as the foundation of a guidance system to help individuals get from one point to another, particularly when they are lost. AHE has lost its way. It needs a GPS.

It is wandering aimlessly from one crisis to the next. Headline after headline decries its loss of effectiveness in serving the needs of American society, its declining support in public circles, and its strident and stubborn insularity.

In article after article, questions are raised about the declining confidence of American society in higher education, and the seeming indifference of AHE to the external demands for change. The internal conflicts among the primary actors within AHE are laid bare to the public, exposing all to criticism and contempt.

Comparisons between education for life and career education are plentiful. The philosophical and theoretical bases for liberal and professional education are made public for everyone to pick a side.

In analysis after analysis critics and proponents explore hypotheses about the rising cost of higher education, the short and long-term effects of the staggering debt load that students and institutions are accumulating, the commercialization of higher education, and the adjunctification of the faculty.

Thirdly, lodestars are models of propriety. They live by fixed values and principles, no matter what the cost to them or their institutions. Currently, it seems that every week brings another scandal to light in American higher education. No segment of AHE has escaped unscathed.

Finally, a lodestar is an inspirational leader. I challenge you to name one individual in educational circles today who inspires others to follow him or her.

Individual campuses may have local lodestars. However, where are the likes of Ernie Boyer, Lee Shulman, John Dewey, Mortimer Adler, Maria Montessori, Paulo Freire, Bertrand Russell, Maxine Greene, B. F. Skinner, James Conant, and Martin Buber? At this junction of time, the enterprise of American higher education has no one individual who stands out ahead of the rest of the field.

As I was pulling my thoughts together for this post, a political/media circus in America made the term lodestar a laughing matter and a joke. How could I seriously use it in this post about American higher education? I decided that I could use it, and must use it because it is the right word to use.

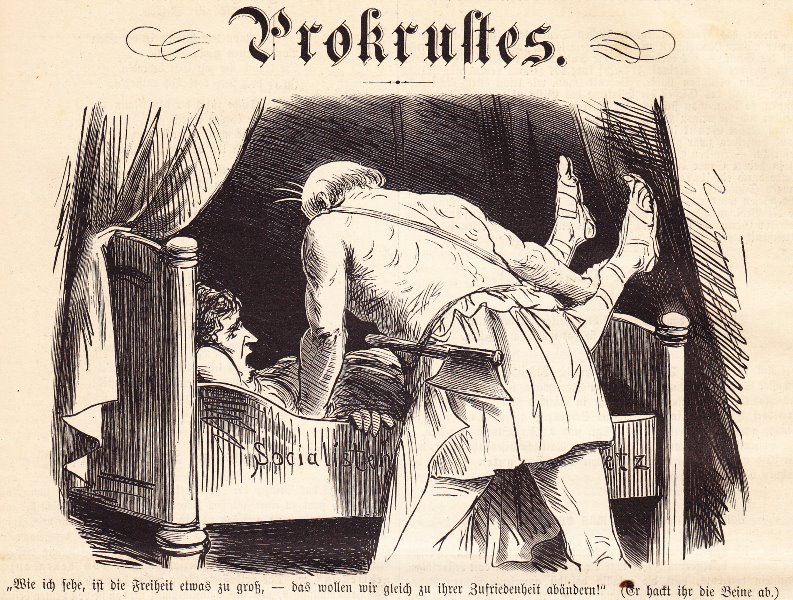

Having settled on the inclusion of the word lodestar, there were still two major stumbling blocks with respect to this post. The first related to the format I have used in all my recent posts. After I translated the pictures in my head into words, I took another step. Since I am not an artist and can’t draw an intelligible sketch of anything, I went and found free pictures that would duplicate as closely as possible the visions in my head. I did this to help my readers understand my thought processes.

In this case, I drew a complete blank. I found nothing that came close to communicating my thoughts. Thus, I have no visual robes to wrap around my verbal thoughts. I decided to go ahead and present the unadorned thoughts to my readers. I do have one question for my readers: Which style do you prefer? The verbal thoughts augmented with pictures, or the naked thoughts by themselves? Please tell me in the comment in the box below. I will use this rough survey to help me determine how I will proceed with my future posts. The second stumbling block was the 1,000-word limit. This will require multiple posts on this topic which will follow in future weeks.

In my next post, scheduled for publication on Tuesday, October 23, I return to my roots as a mathematician and an institutional researcher. I will introduce a new Key Performance Indicator (KPI) that I developed. I call it the Admissions Multiplier Effect. I believe it provides important information that is not otherwise available and should be featured on the dashboard of every institution of higher education.