My previous post, The Commercialization of American Higher Education – Part I, ended with the majority of American colleges and universities languishing in dire economic straits. How can this be? What is wrong with this picture? The American higher education system is arguably the best educational system in the world. It is located in what is generally considered the wealthiest nation in the world. How could more than half of American colleges and universities have financial troubles? How could they not have enough funds in order to operate effectively?

I believe my previous post demonstrated conclusively that many colleges have run out of available funds. They have essentially depleted four of the major sources of resources that I outlined in previous posts. They have exhausted their ability to get more funds from tuition and fees, public support, donors, or endowments. They are operating on fumes. Their fuel gauges read empty or almost empty. Some switched to their reserve tanks years ago. They are now facing the monster in the closet to which Derek Bok alluded in his book Universities in the Market Place: The Commercialization of Higher Education.

Bok argues that American higher education struck a Faustian bargain with corporate America to sell its soul for the necessary funds in order to operate effectively. Is Bok suggesting that some of the smartest minds at some of the best colleges and universities in the world have been outwitted by Mephistopheles? Where’s Daniel Webster when you need him? For the past four decades, American higher education has faced an intimidating trilemma: 1) outsource some operations in an attempt to save money; 2) dive deep into the pool of auxiliary enterprises to make money; or 3) bite the bullet and sell off some of its valuable assets.

In higher education as in any business-like operation, outsourcing is the practice of contracting with an individual or company outside of the college or university to provide goods or perform services which had previously been done by employees of the institution. When it is applied to functions that are not considered auxiliary enterprises, the intent is usually to save money or provide increased quality or uniformity of service. When it is applied to functions that are considered auxiliary enterprises, the intent can be to increase the profits generated by these operations.

The process of subcontracting particular work and jobs to specialists dates back to the 19th century. Outsourcing did not appear as a formal strategy until after WWII. During my days as an undergraduate college student in the 1960s, several of my computer science faculty talked about it as the future of computing.

The term was not widely adopted until the 1980s. My first encounter with the word in an educational-related work setting was in the late 1980s. After 20 years of service in his leadership role, the president of our college went to his first conference of college presidents. He came back very enthusiastic and excited. He had heard a new word and learned of a process which had the “potential to revolutionize higher education.” The word was “Outsourcing”.

Since I was Director of Institutional Research and Planning, he asked me to find potential functions and providers which could serve a college in an outsourcing role. In less than a week, I was able to come up with a spreadsheet with more than 100 different functional operations and appropriate providers for each. Even in the early days of outsourcing within higher education, I was not surprised to find such a large list. The possible functions and potential providers have only multiplied since then.

My list included operations such as Admissions and Student Recruitment, Bookstore, Campus Housing and Residence Life, Campus Security and Public Safety, Campus Signage and Wayfinding, Computing Services and Information Technology, Course Development and Instructional Design, Endowment Accounting and Management, Event Management and Ticket Servicing, Faculty and Staff Recruitment, Financial Aid Accounting and Management, Food Services, Fund Raising, Health and Nonacademic Counseling Services, House Keeping and Building Maintenance, Human Resources, Insurance and Risk Management, Lawn Services and Ground Maintenance, Marketing and Public Relations, Payroll, Procurement, Recreational and Fitness Center Management, Student Accounts and Receivables, Transportation and Vehicle Maintenance, and lastly, Vending Operations.

One fascinating function on my list was a local firm which advertised that they would “service” live plants inside your public buildings. They would place their plants in strategic locations, guaranteeing to beautify and spruce up your facilities. They would come once a week to check on their plants. They would water and feed them as necessary. If their plants started wilting or dying, they would replace them with healthy ones to keep your buildings green and clean. This definitely seemed to be a candidate for outsourcing.

Although everyone knew that beautiful, live plants created a welcoming atmosphere to visitors, most office staff paid little attention to the plants just outside their offices, except to complain about how bad they looked when they were wilted or dead. Those staff members who did water the plants often over-watered them, creating a mess on the floor, which housekeeping had to clean up.

There’s a common maxim in organizational theory: “When everybody is responsible, then nobody is responsible.” The Disney Corporation’s ubiquitous Culture of Excellence is the most obvious example of an organization that has instilled a pervasive sense of responsibility in all employees. If an institution is not ready to go “full-speed ahead” with the adoption of the Disney approach to all operations, then functions which are mission-marginal become prime candidates for outsourcing.

I added notes to my database indicating what I saw as potential red flags for some of the possible functions. I believed some activities such as Admissions, Course Development, Faculty Recruitment, Fund Raising, and Residence Life, were too close to the center of our educational mission as a Christian college to relinquish any control over. No matter how well the outsourcing contract is written, when you turn over a function, in total or in part, to an outside vendor, you lose some control over it.

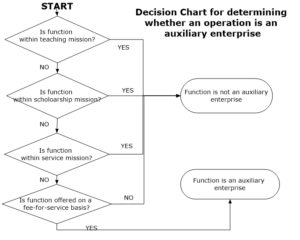

Before we turn our attention to auxiliary enterprises, remember that in higher education accounting parlance, auxiliary enterprises are operations that must satisfy two criteria. The first criterion may be the most important. Auxiliary enterprises must be outside the primary mission of the educational institution. In American higher education, it is usually assumed that the mission of a college or university revolves around the triad of teaching, scholarship, and public service. Anything outside all three of those areas is a candidate for classification as an auxiliary enterprise. Anything inside one or more of the areas cannot be considered an auxiliary enterprise. The second criterion which an auxiliary enterprise must satisfy is that it provides goods or services to individuals or groups on a fee-for-service basis. As an accepted consequence, these enterprises are meant to be profit-making or at least self-supporting. They are definitely not intended to be a drain on the institution’s resources, particularly its general and education budget.

The classification of some operations as auxiliary enterprises is obvious, while the classification of other operations is debatable. The key to the classification of an operation as an auxiliary enterprise is the satisfaction of the two criteria. Firstly, the enterprise must reside outside the primary mission of the institution. Can the institution fulfill its mission of teaching, research, and public service without relying on this operation? Secondly, does the enterprise charge on a fee-for-service basis with the intent of making a profit or at least breaking even?

The first example of an auxiliary enterprise which I want to consider is campus housing. For many years, it had the highest, consistent profit potential of any auxiliary enterprise. I can already hear the catcalls from the proponents of residential education yelling, “Residence life is an essential component of the teaching mission of our college.” However, with the exception of a handful of special mission institutions like the military academies and experimental institutions like Deep Springs College in California, almost all colleges and universities can fulfill their teaching mission without requiring students to reside in campus housing.

The first example of an auxiliary enterprise which I want to consider is campus housing. For many years, it had the highest, consistent profit potential of any auxiliary enterprise. I can already hear the catcalls from the proponents of residential education yelling, “Residence life is an essential component of the teaching mission of our college.” However, with the exception of a handful of special mission institutions like the military academies and experimental institutions like Deep Springs College in California, almost all colleges and universities can fulfill their teaching mission without requiring students to reside in campus housing.

Why do colleges which claim campus residence is a requirement make exceptions? There are two primary reasons. Firstly, although to my knowledge the requirement has never been tested in a court of law, many legal scholars believe that it would be a very difficult for most institutions to prove that residency is a real necessity in order to meet their educational goals for students. The only exception would be schools like the military academies which actually demand a 24/7 living-learning experience as a part of their educational requirements. Secondly, most institutions need students. Bending on the residency requirement is one way to enroll more students.

In order to establish the fact that campus housing is an auxiliary enterprise, I have the following evidence to present. I would like to call to the witness stand the colleges that “require” first-year students to reside on campus. I realize that in any trial situation, I cannot require defendants to testify against themselves. I can use their publicly communicated words against them.

It’s happened again. I’ve run out of time and space to finish my discussion of campus housing as a prime example of using auxiliary enterprises to provide a buffer to a college’s budget woes. I didn’t even get to a discussion of other auxiliary enterprises, examples of how outsourcing could help colleges, or examples of the positives and negatives of the sale of institutional assets. My next post The Commercialization of American Higher Education – Part III will continue the discussion of campus housing. I will consider other auxiliary enterprises in Part IV. I will deal with outsourcing in more detail in Part V, and sales of assets in Part VI.

The benefits of required housing ended when In Loco Parentis was abandoned.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_loco_parentis

I view ”adjunct” instructors as a form of outsourcing. While bringing professionals from the world of work into the classroom can definitely enhance students’ learning, an over-abundance of adjuncts can hurt continuity of a program.